My Take Tuesday: “Doc, whatever she has, I’ve got the same thing too!”

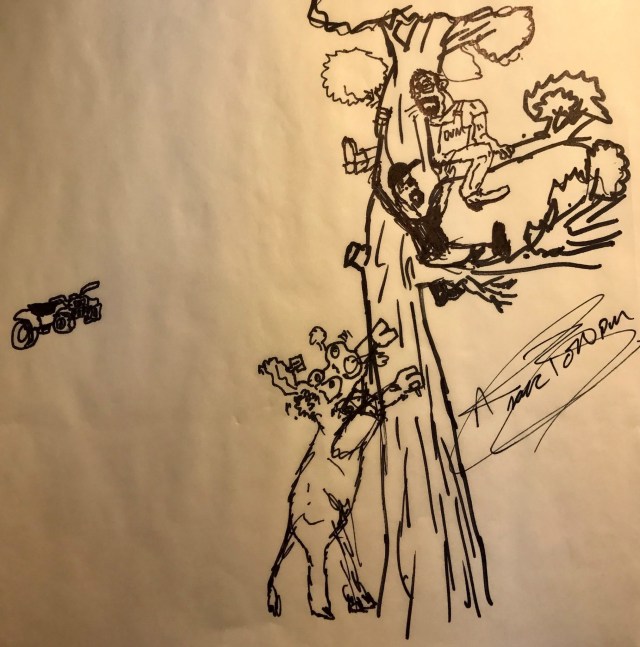

Animals and people dictate what happens every day for me. Simple routine appointments can turn out to be complex once the unpredictable yet potent potion of human personality is added to the mix.

A few months back an elderly woman came in to the clinic. Her cat had been suffering for weeks with non-stop itching. As I examined the cat I noticed that this itch was insatiable. The poor cat had scratched and irritated nearly every inch of its body in an effort to satisfy the intense itch. The scratching was so intense, that nearly her entire body was covered with bleeding sores.

A diagnosis of mites was made after taking a skin scrape and looking at it under a microscope. This particular mite is elusive and difficult to find even for the most experienced veterinary dermatologists. However, it is highly contagious.

As I began speaking with the owner about the severity of the diagnosis and the need for immediate treatment, I could tell that her mind was wandering. She was clearly not focusing on what I was saying. I politely asked if I had said something that did not make sense or if she had any questions. Often, the open ended questions will allow a client to discuss their concerns, however, I was not prepared for what happened next.

“Doc, do you think I have what she has?”, her voice was inquisitive. “Excuse me?”, I replied, “What do you mean?” Before I could say another word, this elderly woman dropped her pants. Literally right to the floor. Her legs were covered in large red lesions. They actually looked like checker boards. I learned that day, albeit involuntarily, what “granny panties” look like.

I am easily embarrassed, and when this happens my face turns a deep red. I stammered, “I…. I’m… a… I am sorry ma’am, you will have to go to your doctor for that”. The beet-red shade on my face persisted even after I exited the room.

As crazy as this may seem, I have had worse things happen while going about my daily appointments. However, those are saved for another My Take Tuesday.

My job is never boring. The two legged creatures that come in keep it from ever being so.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

My Take Tuesday: The Red Handkerchief

My Take Tuesday: The Red Handkerchief