My Take Tuesday: The Cooper of Castle Valley

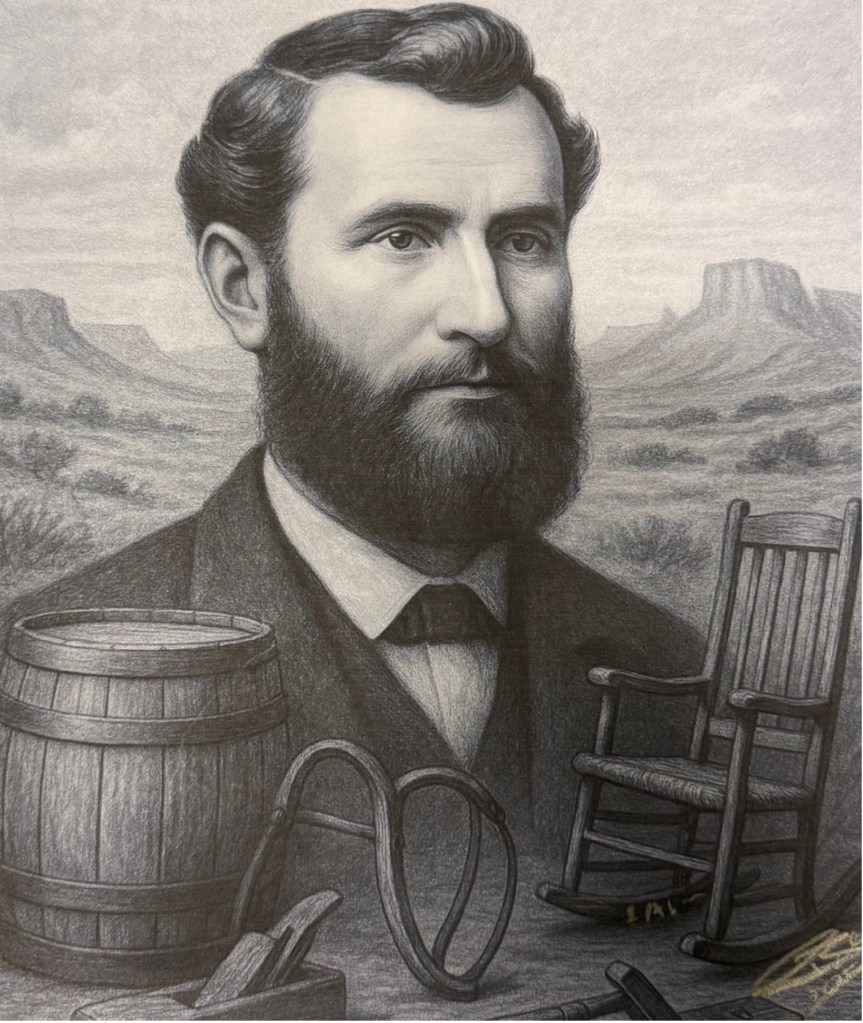

Some people leave behind great monuments—statues, buildings, legacies etched in stone. My great-great-grandfather, Boye Petersen, left behind a barrel. And a yoke. And a Bible with a handwritten prayer tucked inside. No marble. No bronze. Just wood, faith, and a life lived with quiet purpose.

Boye was born in Ribe County, Denmark in 1841. A master cooper by trade, he made barrels with skill and precision. But barrel-making was just the beginning. In 1872, with his wife, Mette Kjerstine, and their four young children, he boarded the S.S. Nevada and set sail for America—a land of promise, hardship, and deep conviction. They left comfort behind for faith, choosing Zion over familiarity.

The family first settled in Fountain Green, Utah, where more children were born, including my great grandmother. But their journey wasn’t finished. On August 27, 1879, they packed their belongings once again—this time at the urging of church leadership—and traveled across rugged terrain to the sparse, wind-swept plains of Castle Valley in Emery County. They arrived in Castle Dale on August 31.

There, Boye built a modest two-room log cabin. He would live out the rest of his life within those simple walls. After his death, his daughter Rebecca raised fourteen children in that same cabin.

The land was not generous. Even today, Castle Dale’s soil struggles to yield much. But Boye never complained. He worked those 40 acres as though he’d been entrusted with the Garden of Eden. This piece of land remains in the family until this day.

He knew grief all too well. Of his twelve children, eight died young. Yet those who knew him spoke not of bitterness, but of his strength, reverence, and unwavering work ethic. He served as a traveling church judge, riding from town to town to help settle serious matters. He worked frequently in the Manti Temple, making the long journey by horse and buggy over the mountains in just six or seven hours. When people marveled at his speed, he’d smile and say, “Why drive oxen when you have horses?”

Each week, he carried water from the ditch—ten gallons at a time—using a wooden yoke he had built to fit across his shoulders, buckets swinging from ropes on either side. Today, that yoke sits in the Castle Dale Museum. More than a relic, it stands as a quiet emblem of the life he lived: steady, balanced, intentional.

Boye was a craftsman in every sense. He built rocking chairs, workbenches, and furniture that still grace family homes to this day. He never used metal—only wood, expertly joined with wooden screws and pins. He kept his workshop spotless. My great-grandfather would tell stories of how Boye could walk into that shop on the darkest night and, by touch alone, find any tool he needed.

And then there was his Bible. Worn and richly illustrated, it featured side-by-side translations of the New Testament—1611 and 1881 editions. My grandfather recalled sitting beside his father, turning its pages, listening to stories drawn from its depths.

Tucked within that Bible is a handwritten prayer. Boye wrote:

“I, Boye P. Petersen, most humbly pray thee, O Lord, to give me grace to always adhere to the truth and have my mind quickened by the Holy Ghost so that I might always be able to decide between Truth and Error, and to have Courage to Defend the Principles of the Gospel of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”

That prayer still humbles me.

Boye passed away in December 1912—nearly seventy years before I was born. And yet, through his workmanship, his quiet devotion, and the stories that have shaped my family for generations, I feel as though I’ve come to know him. In truth, he never really left.

Some men build empires. My great-great-grandfather built barrels—strong, watertight, and true. Much like the life he lived: humble in form, enduring in purpose.

And That is My Take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Wonderful story! Can’t leave a better legacy than that ❤️❤️

LikeLike