My Take Tuesday: Where Memory Still Lives

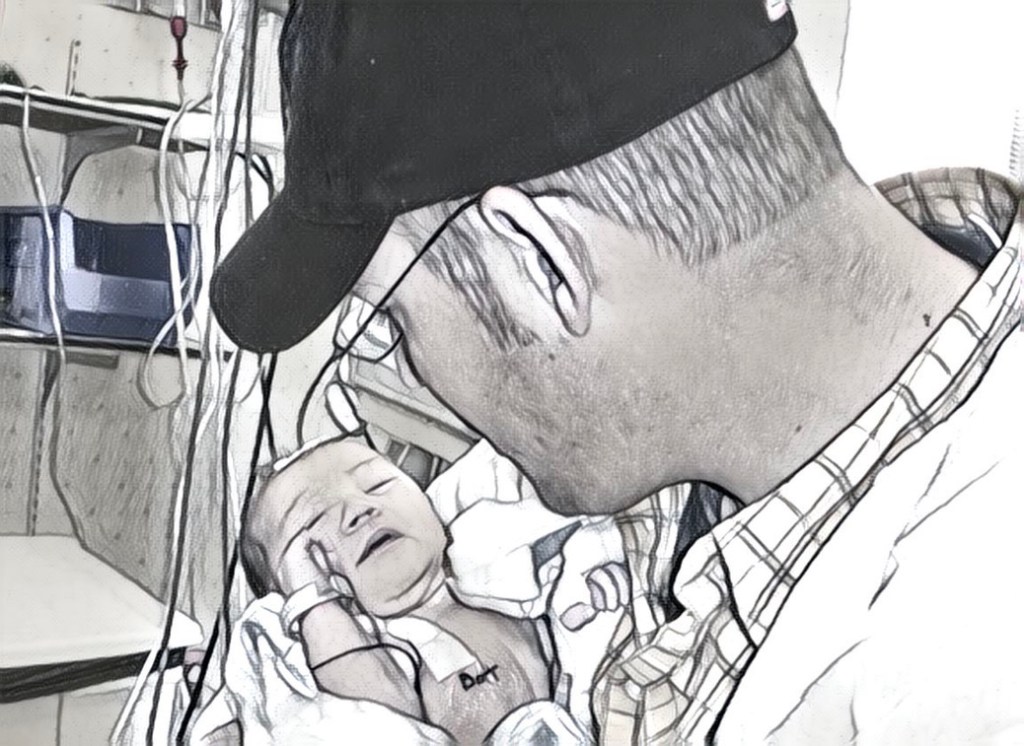

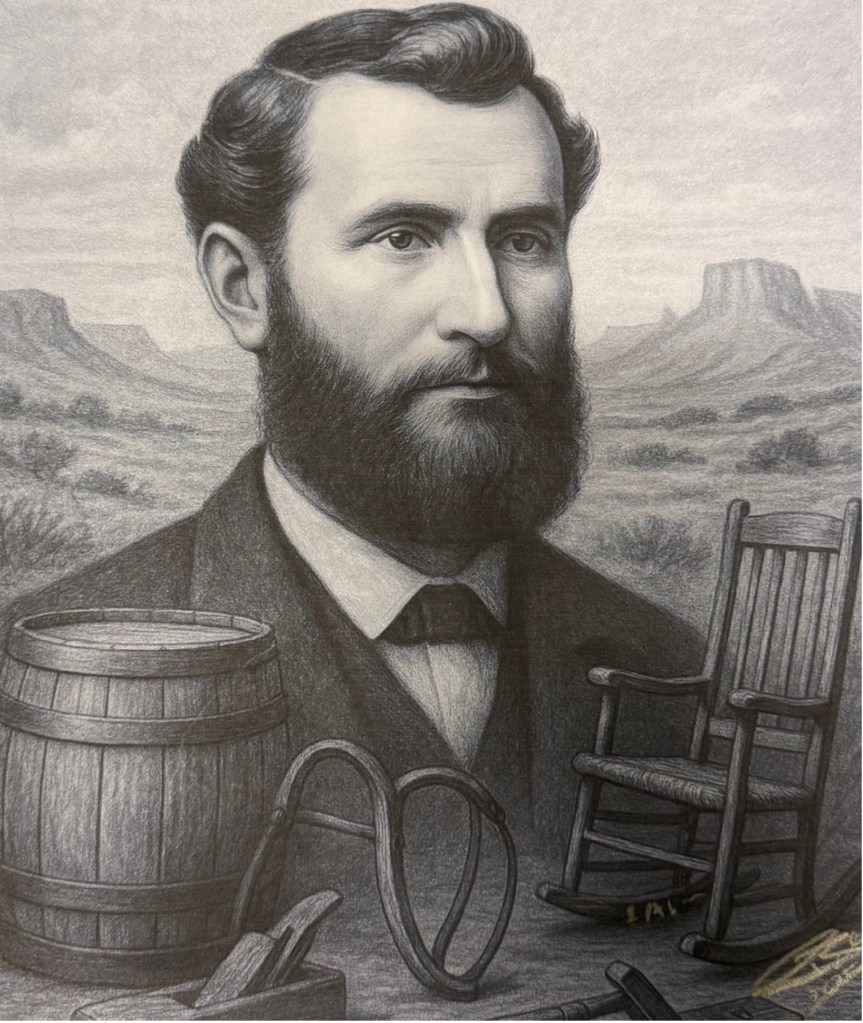

(In Loving Memory of Hugh and Shonna Peterson)

It was a still summer evening—the kind that gently wraps around your shoulders like a well-worn quilt. The sun, slow and sure, crept behind the mountains west of Emery, Utah, casting its final light across the sky in a hush of gratitude. Crimson melted into orange, orange into violet, and the heavens blushed with color as if remembering something beautiful.

I stood barefoot on the lawn outside the old adobe brick house—my grandparents’ house—on the corner of 200 North and Center Street. The cottonwoods towered above me, their leaves whispering secrets I’ve known since childhood. Their scent—rich, earthy, and sweet—mingled with the breeze, alive with memory.

To the south, the garden still grows in my mind’s eye: corn, cucumbers, zucchini, peas, and potatoes, with bright marigolds planted just so. It wasn’t just a patch of cultivated earth. It was a canvas of care, painted by my grandparents’ hands with quiet diligence and deep affection. The air smelled of soil and cut grass, of salt grass and blue clay, tinged with the trace of baking bread, lilacs by the back fence, and coffee on the stove. These were the smells of Emery. The smells of home.

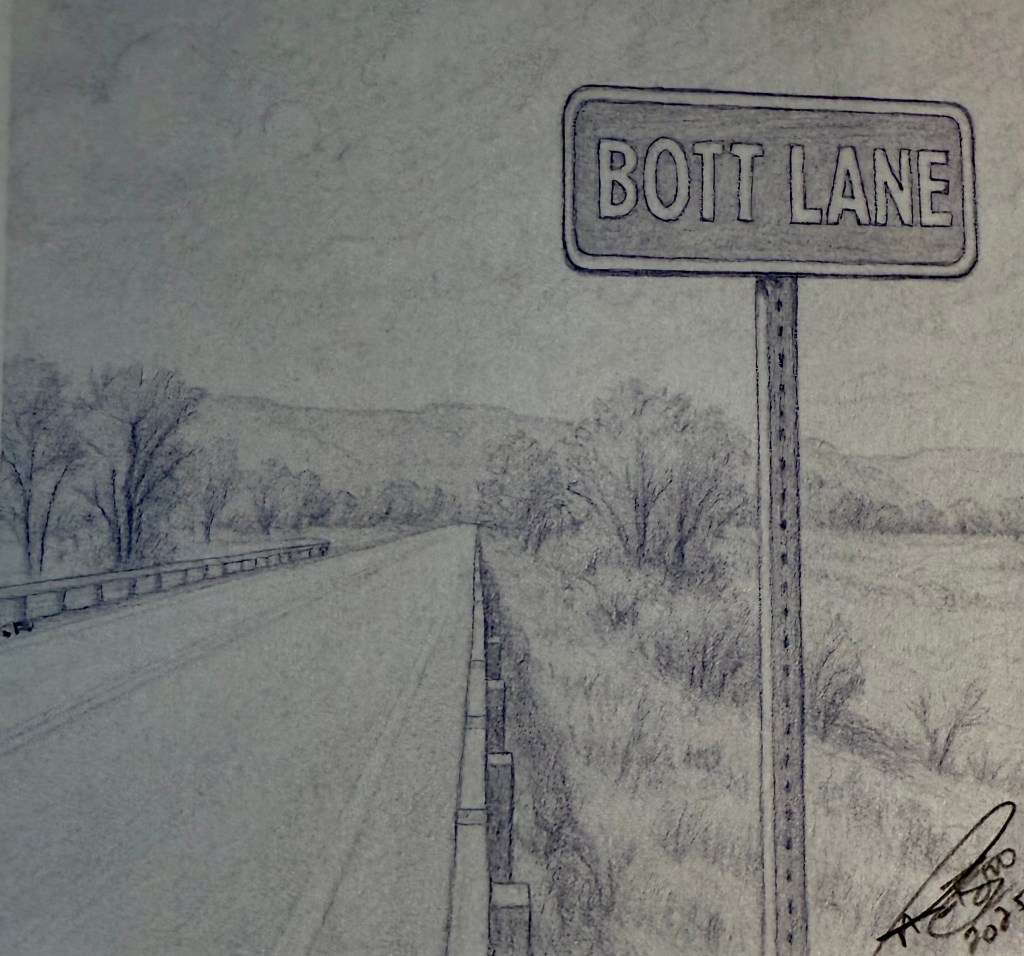

Just north of town, where Muddy Creek winds its quiet way, lies a hidden oasis—a sacred corner of the earth where my grandfather, Hugh Peterson, once worked the land. That soil knew his boots. That breeze carried his voice. And though he and Grandma Shonna are gone now, I still feel them there—in the hush of the cottonwoods, in the warmth of the bricks, in the very soul of that home.

A single photo—humble and still—can hold so much more than it shows. A stretch of lawn. A front porch. A weathered birdbath and a ceramic swan. But if you look closer, you can see birthday parties and Sunday dinners, afternoon naps, and children catching grasshoppers in the garden. Every element tells a quiet story of love, care, and homegrown charm.

But the true magic began once you stepped inside.

The green shag carpet clung faithfully to the stairs, each tread worn smooth by decades of footfalls—bare feet in summer, stocking feet in winter, little feet bounding upward in search of cousins and comfort. The walls, painted and paneled, held the warmth of years gone by. In the kitchen, a calendar held notes written in my grandmother’s steady hand, her script as familiar to me as the sound of her voice. Every family member’s birthday and anniversary were handwritten.

Upstairs, the bedrooms waited in gentle stillness. A bed made with floral sheets and hand-stitched quilts. A cedar chest stacked with books and records. Pictures lined the walls of the bedrooms and staircase. The scent of linen and wood and time. It was a room filled with softness, where silence felt like comfort and love rested in every fold of the blanket.

And then there was the living room – drenched in golden sunlight, filtered through lace curtains that swayed with even the slightest breeze. The rust-orange carpet was bold and unapologetic, layered with the footsteps and laughter of decades. The furniture—perfectly mismatched—held stories of its own. The leopard-print armrests on grandma’s chair, handmade afghans, a sunflower pillow, a golden rocking chair with sunken cushions. A wooden clock ticked gently on the wall. The television, rarely watched, sat below framed portraits, porcelain figurines, and plaques bearing quiet declarations of faith. It wasn’t décor. It was devotion.

This house, this corner of Emery, was my Eden.

It was not fancy, but it was full—of sacrifice and sweetness, of sweet rolls and Saturday chores, of country music on a dusty AM radio, of Grandpa’s humor and wisdom and Grandma’s radiant kindness. The house had a heartbeat. You could feel it in the hush of the morning, in the creak of a step, in the hum of the Stokermatic furnace, and in the warmth of the people who made it home.

Even now, years later, if I feel worn down or a little lost, I return here—not in person, more often in memory. I climb those stairs in my mind. I walk barefoot across the rug. I stand again in the living room’s golden light, and for a moment, I am whole.

This home taught me how to love. How to slow down. How to belong.

If you ever need to remember what really matters, take a quiet drive through Emery, Utah. Stop at the corner of 200 North and Center Street. Stand beneath the cottonwoods. Let the wind carry their voices. Step onto the porch. Listen closely.

You’ll know what I mean.

Because love never leaves the place it made its home.

And that is My Take!

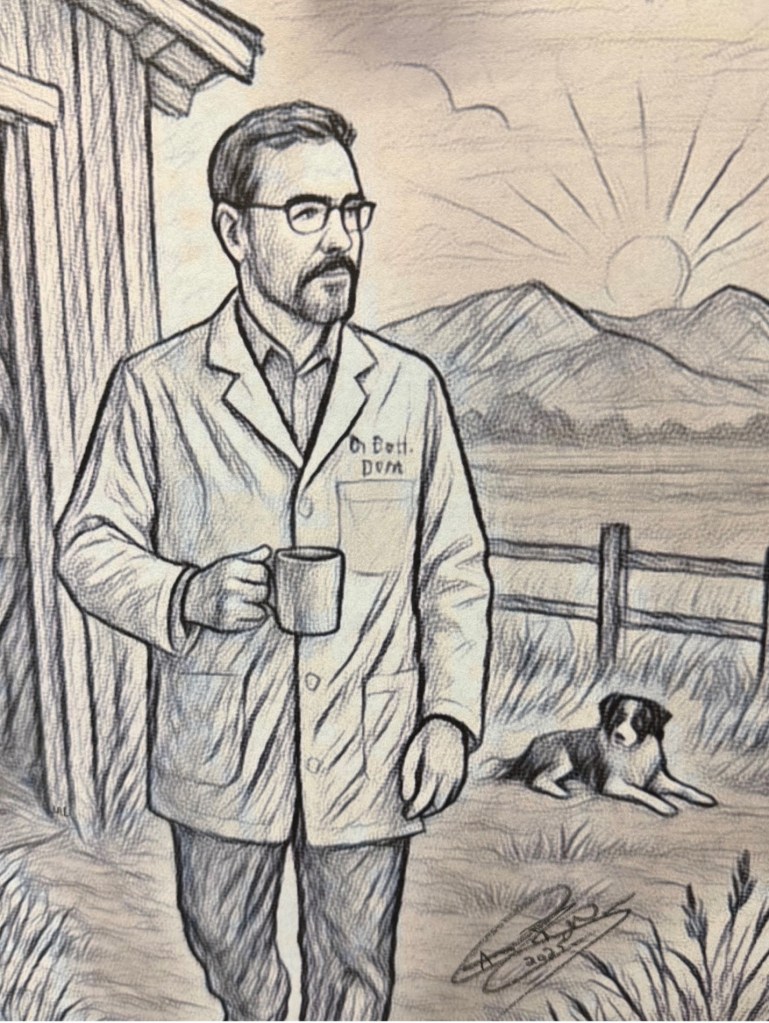

N. Isaac Bott, DVM