Category: Uncategorized

Reflection

My Take Tuesday: Reflection

The wind howled, its lonesome lullaby piercing my ears as I turned up my coat collar. The desolate country lay still, with its towering stone cliffs and sage brush interrupted only occasionally by small clumps of cedar trees. The trail I was climbing was built by the CCC project (Civilian Conservation Corps) in the 1930’s during the Great Depression. The winding trail jots back and forth in a switchback as it leads to the south end of Trail Mountain.

I stood in awe as I gazed at the clear smooth reflective surface of Joe’s Valley Reservoir. The water was as smooth as glass and the towering mountains seemed to peer back from the water.

I have so many childhood memories of hiking this trail with my family, of fishing in the lake below and of family reunions with loved ones who are no longer here.

This is home. There is something about Emery County that heals my soul. This is my constancy and my serene sanctuary where I can reflect and recharge.

At its simplest, reflection is about careful thought. But the kind of reflection that is most valuable is more nuanced than that. The most useful reflection involves the conscious consideration and analysis of beliefs and actions for the purpose of learning. Reflection gives the brain an opportunity to pause amidst the chaos, untangle and sort through observations and experiences, consider multiple possible interpretations, and create meaning. This meaning becomes learning, which can then inform future mindsets and actions.

A reflective period need not be a time to be unduly harsh with ourselves, but rather to be lovingly honest. Firm yet forgiving. After all, endless rumination and self-recrimination keeps us trapped in a past we cannot change, and no one benefits from this. An attitude of self-forgiveness can liberate us from old patterns or ways of being that we likely adopted for a reason, but that do not serve us nor adequately reflect who we are and who we’d like to be.

Taking time to reflect will most certainly help you recharge. It will help you refocus and it will bring feelings of gratitude and purpose that are otherwise never experienced.

Try it. You will not regret it.

If you need a spot, there is a place along the CCC trail high above the world’s most beautiful reservoir just west of Castle Dale, Utah.

And at is My Take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Yo Quiero Bite You

My Take Tuesday: Yo quiero bite you!

Often “the question” comes up during a routine appointment. Curiosity is naturally sparked with my response.

The question is, succinctly put, “Doc, what breed of dog bites you the most?”

The answer is unequivocally the chihuahua. Of the dozens of bites that I have received, a vast majority came from chihuahuas.

Chihuahuas are comical, entertaining, and loyal little dogs, absolutely brimming with personality – often a quirky and eccentric personality unmatched by any other breed.

Some of my sweetest patients are chihuahuas. They are affectionate and loving.

But every once in a while, a mean one comes along.

While a bite from a Chihuahua isn’t going to inflict the same damage as a bite from a larger dog like a pit bull or boxer, it can still leave a painful wound that’s prone to infection. There’s an old myth that a dog’s mouth is cleaner than a human’s mouth, but this isn’t a true. Whenever a pet bites, there is significant risk of infection.

While Chihuahuas are not naturally more aggressive than any other breed, they seem to be prone to react with aggression out of fear. Veterinarians are often the target of such aggression, simply because dogs are fearful of unfamiliar people and situations.

As a recent graduate, I was learning how to diagnose, treat and cure the routine cases that present daily. I had only been a veterinarian for about a month when I learned my lesson.

It was a routine appointment. Annual vaccinations and a wellness exam were needed. As I entered the room, Chispa, sat on the table glaring at me. As I reached down to auscult the heart and lungs, Chispa absolutely went ballistic. Within 5 seconds, she had peed and soiled all over the table top. Instinctively, I reached for a muzzle. As I attempted to place the muzzle on her, she absolutely lost it.

Just like a loud clap of thunder that follows a flash of lightning; when I am bit by a dog, imprecations are sure to follow.

Chispa sunk her needle like teeth into my right hand and bit me again and again.

Before I could even mutter the phrase, “Oh S#*!”, this little devil had bitten me three times.

Her only goal seemed to be to inflict as much damage as possible to the man in a white coat that was reaching for her.

Blood poured down my hand. I sat stunned. I have fast reflexes; after all, I dodge bites and scratches on a daily basis.

What was different about this experience? Perhaps it was in the name. “Chispa ” is a Spanish word meaning “spark”. Certainly, the fiery personality and name fit this small canine.

The rapidity of the attack taught me a lesson. I am much more careful now when dealing with seemingly innocent small pets. I do my best to reduce the fear and anxiety that accompanies a visit to the veterinarian.

And I am especially careful with pets that have incendiary names such as Diablo, Fuego, Demonio and, believe it or not, Fluffy.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

DocBott Got Ran Over By a Reindeer

My Take Tuesday: DocBott got ran over by a reindeer!

Many of the pictures I post are of Mountain West Animal Hospital’s resident reindeer. They are very docile and love the attention. Sven and Yuki will pose for photos and love little children. Sven even has a fondness for the color pink.

However, not all reindeer are like this. A male reindeer’s personality changes dramatically as the breeding season approaches. Rising testosterone levels in the male reindeer are responsible for the hardening and cleaning off of the antlers. This cleaning off of the velvet has an abrupt onset. Although fresh blood is noted on the antlers as the velvet comes off, the condition is NOT PAINFUL. There is no sensation in the antlers at this point.

Testosterone will make an otherwise tame male become a raging, grunting and aggressive mess.

A couple of years ago, I received a call from a reindeer farmer in northern Utah. He had a male reindeer that has injured the base of his antler. August heat and fresh blood are a recipe for complications due to either a severe bacterial infection and/or disgusting maggots.

I arrived at the farm and immediately realized that the bull was in full rut. I had just left the office and, like a true nerd, had placed an external hard drive for my computer in my front pocket.

The bull was not very happy to be caught. It took three of us to restrain him while I treated his injury. His massive antlers could easily lift us off the ground and fling us in any direction desired.

Just as I finished the treatment, he broke lose. He immediately turned toward me. I had very little time to react. I stood there with empty syringes and iodine in my hands, helpless and very much vulnerable. His attack was swift. A single charge knocked me on the ground.

I lay there struggling to catch my breath. The sudden impact of the ground on my back left me with temporary paralysis of the diaphragm which made it difficult to take a breath. When I finally did breathe, I was bombarded with excruciating pain over the left side of my chest. I reached into my pocket and removed the external hard drive. It was shattered.

I was very much defeated and beaten, but overall ok after I got on my feet. The pain was caused from two cracked ribs. Other than that, I had no further damage from the incident.

I learned my lesson that day. rutting reindeer cannot be trusted. They are the most dangerous animal I have ever worked with. They make a Jersey dairy bull seem like a young puppy.

I am glad I had the external hard drive in my pocket. The antlers would have easily punctured my lung and inflicted life threatening injuries.

If you ever see a male reindeer grunting, snorting and peeing on itself – STAY AWAY!

You have been warned.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

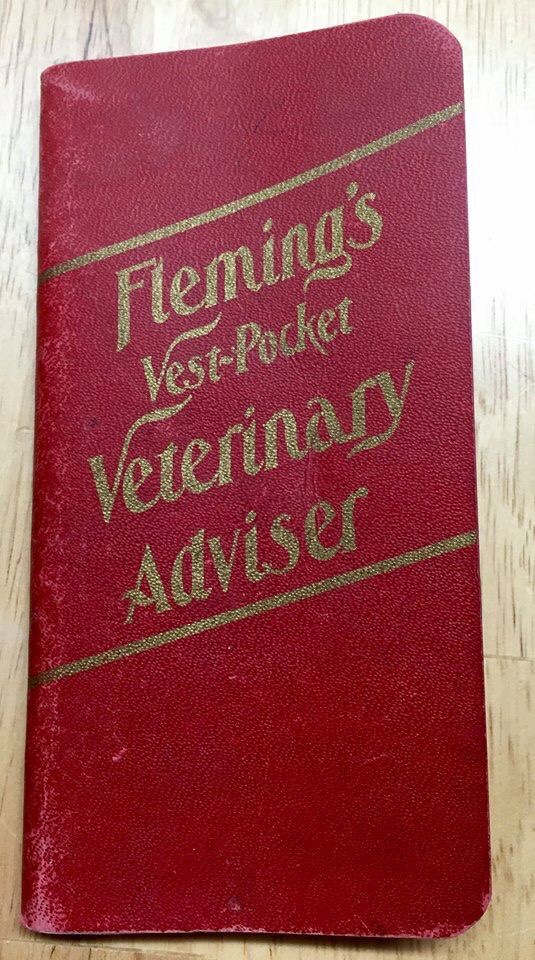

Fleming’s Vest-Pocket Veterinary Adviser

My Take Tuesday: Fleming’s Vest-Pocket Veterinary Adviser

The year was 1904. The town of Emery, Utah had a population of around 560 people, nearly double what it has today. Emery has always been an agricultural community. Ranching and farming are as much a part of its scenery as the towering cliffs that overlook the small town. Visitors are often taken aback by the beauty and expanse of this beautiful country on the edge of the San Rafael Swell.

Lewis W. Peterson made his living as a farmer. Life during this time could not have been easy. Lewis and his young wife experienced extreme heartbreak during their first few years together. Their only two children at the time would die from an influenza outbreak that indiscriminately killed so many in this small community in 1907.

The remote location of the town isolated it somewhat from other communities. The town had a fine yellow church house that had a large ballroom floor that served not only for Sunday worship services, but also for social gatherings. This building still stands in the center of town today.

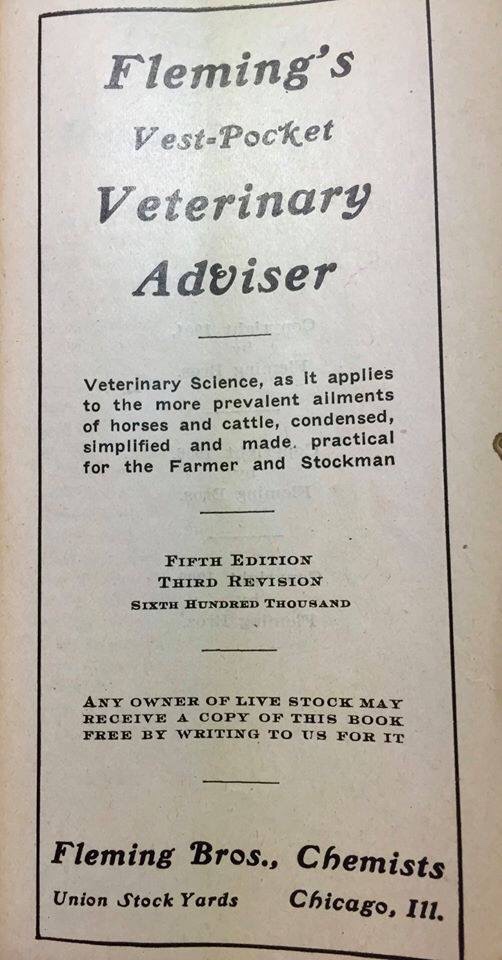

Information came in the form of newspapers and books. Knowledge was a valuable asset that would set certain farmers apart. When information was available, these farmers were open to reading and learning. It was during this time that LW Peterson acquired a new book called, Fleming’s Vest-Pocket Veterinary Adviser.

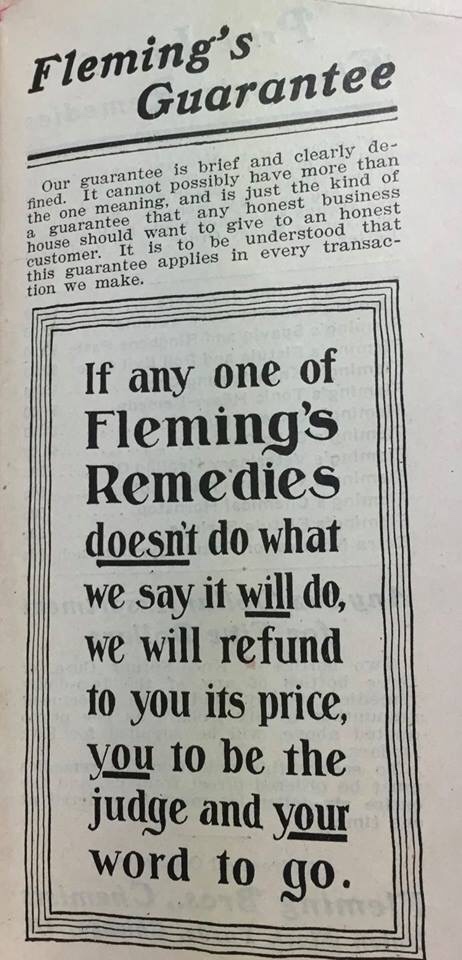

This now 114 year old, pocket size handbook of veterinary information pertained to diseases of horses and cattle, and was designed to help farmers and stockman. It provided 192 pages of everything from birth to aging, to caring for illnesses, to poisonous weeds, maintenance, how to feed, and recipes for concoctions to treat a variety of ailments.

This book must have helped LW. He kept the book. He passed it down to his son, Kenneth Peterson, who passed it to his son Hugh Peterson.

My grandfather, Hugh Peterson, gave it to my mother, who gave it to me. This book is displayed prominently in the museum case in the reception area of Mountain West Animal Hospital.

The well worn pages of this book are fascinating to read through. Although veterinary science was in its infancy at this time, it is still interesting to read about treatments used. Without the luxuries of modern antibiotics, antiseptics, anesthetics and anti-inflammatories, these treatments were innovative for their time. The early 1900’s provided incredible advances in hygiene practices, preventive medicine concepts evolved, the first vaccines appeared, nutrition was studied and research was beginning to show which therapeutics actually worked, and why.

Perhaps some would consider this dated literature obsolete. Much of the information contained therein certainly would be considered so. I, however, consider it a treasure. I wonder if LW realized that, more than 60 years after his death, a veterinarian, carrying 1/16th of his DNA, would appreciate this book passed from generation to generation.

I will keep this book safe and pass it on to my children. Who knows, perhaps in another 100 years, it will still be seen as a valuable piece of family and veterinary history.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Chickens

My Take Tuesday: Chickens

If you attended elementary school with me, you will probably will remember my obsession with chickens. As a child, I would draw chickens when I was bored. Given the many drawing projects that elementary age children have, I drew hundreds of mediocre pictures of my pet chickens. Fortunately, my teachers were patient and supportive. Although my artistic abilities left much to be desired, I was free to draw to my hearts content.

We would receive an annual catalog from Murray McMurray Hatchery. This catalog would depict every conceivable breed of chicken and give a short description of the desirable traits each possessed: comb type, leg feathering, silky, frizzle, bantam, standard, etc. I would spend hours and hours looking through this catalog. Each year, I was allowed to choose a single baby chick of the breed of my choosing. I took this choice seriously.

There are a range of things that one needs to consider when deciding what breed of chicken to have. These include the climate in which you live, whether you are raising backyard chickens for eggs or meat production, their temperament, foraging capability, predator awareness, and broodiness. I meticulously studied each breed and made my selection each year.

Here in the United States, the postal system accepts boxes filled with day-old chicks and delivers them coast to coast with overnight delivery. The chicks travel by Priority Mail and often have no food or water in their cardboard carrier to sustain them. How can this happen? Just prior to hatching, a chick absorbs all the remaining nutrients from within its egg. With this nourishment, the chick can survive for up to three days without food or water. This makes it possible to ship them by mail. In the nest, this process allows the mother to wait out the hatching of other chicks in her clutch before tending to the early hatchers: If chicks required immediate attention, the mother would leave with those that hatched first and the unhatched chicks would perish. This is a fascinating adaptation!

To this day, chickens remain my favorite animals. I look back with fondness on the days spent coloring and drawing with crayons.

Memories are painted optimistically with passing years. I miss the worry-free days sitting at a desk in elementary school.

I will forever treasure these pictures and the pleasant memories associated with them.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Sheep and Stoicism

My Take Tuesday: Sheep and Stoicism

Sheep can be stubborn. I remember as a child trying to herd our small group of ewes to a nearby pasture. Although it was only about a hundred yards away, it didn’t go well. As I turned the sheep out, they all began running in every direction. There was pure chaos. I ended up covered in sheep snot, lying on my back looking up at the blue sky. The sheep were all over town. Not one of them ended up in the desired pasture.

Not long after this, my very wise great uncle, Boyd Bott, taught me an important lesson. The trick was simple: “You can’t herd sheep. You have to lead them.” It is a lesson I will never forget.

Taking a pail of grain and walking out in front of the sheep will yield an opposite response than that described above. The sheep will literally run after you and follow where ever you want them to go. Every time I had to move the sheep from this time forward, it was easy.

Sheep have a strong instinct to follow the sheep in front of them. When one sheep decides to go somewhere, the rest of the flock usually follows, even if it is not a good decision. Humans are the same way. In the bible, sheep are often compared to people. I find this comparison very accurate. We are stubborn. We resist when we are pushed. We follow when we are lead.

There is no better way to learn patience than having a small herd of sheep. They require much attention, protection and care.

Next time you find your patience running thin, think of exercising oversight instead of compulsion. It will most certainly yield a better result.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

This photo is of Dr. Bott holding a newborn lamb on his family farm in 1985.

My Take Tuesday: The Affable Nature of Theriogenologists

My Take Tuesday: The Society for Theriogenology

Greeting from 30,000 feet! This week I am writing from the air. As I peer out the plane window, I see a limitless sky. I love flying! I am en route to Savvanah, Georgia to attend the annual conference of the Society for Theriogenology.

This is an annal event that I have attended since 2007. Each year the meeting is held in a different city around the country. I eagerly await this conference each August.

What is Theriogenology? Theriogenology is the branch of veterinary medicine concerned with reproduction, including the physiology and pathology of male and female reproductive systems of animals and the clinical practice of veterinary obstetrics, gynecology, and andrology. It is analogous to the OBGYN, Neonatologist and Andrologist of human medicine – all combined in a single broad specialization. From antelope to zebras, Theriogenologists work on all species of animals. It is a challenging, unique and rewarding discipline.

I became interested in theriogenology as an undergraduate at Southern Utah University. A professor and mentor named Dan Dail introduced me to this most unique area of veterinary medicine. I learned a lot from him. He entrusted me with a research project looking at the correlation of body condition scores and first service conception rates in heat synchronized beef cattle. His mentorship, along with this research contributed to my acceptance into veterinary school. Dan Dail passed away a few years ago.

At Washington State University, I had the privilege of working extensively with Ahmed Tibary, a world renowned theriogenologist. He has made endless contributions in teaching, published books, chapters and scientific articles. His comparative approach taught me how to think and reason through difficult cases. He also entrusted me with the animals under his care. We published a significant amount of information on reproduction in alpacas. I remember with fondness my time working with him.

My theriogenology work has made me a better veterinarian. My clinical approach has been shaped and molded by the examples of so many mentors and teachers. What drives me is the comparative medicine; that’s what makes my brain move. Whether I am in the clinic working on dogs or cats, or out working with bighorn sheep, elk, alpacas or water buffalo, I am doing what I love.

It is my privilege to serve as the immediate past president of this organization. Upon a cabinet in the lobby of Mountain West Animal Hospital, a small statue sits. The statue depicts a bull named Nandi, the Hindu god of fertility. I am humbled to see my name on the plaque beneath the statue.

Kindness is a commonality among veterinarians who are reproductive specialists. They are approachable and humble. In a profession where arrogance often is the norm, they are a refreshing example of the best of the best. They are among the leadership at nearly every veterinary school in North America. They are leaving a lasting impression on the profession.

I am so proud to be a member of this group.

It has been a tremendous honor for me to serve as immediate-past president of this organization this year.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

My Take Tuesday: Theriogenologists

My Take Tuesday: The Society for Theriogenology

Greeting from 30,000 feet! This week I am writing from the air. As I peer out the plane window, I see a limitless sky. I love flying! I am en route to Savvanah, Georgia to attend the annual conference of the Society for Theriogenology.

This is an annal event that I have attended since 2007. Each year the meeting is held in a different city around the country. I eagerly await this conference each August.

What is Theriogenology? Theriogenology is the branch of veterinary medicine concerned with reproduction, including the physiology and pathology of male and female reproductive systems of animals and the clinical practice of veterinary obstetrics, gynecology, and andrology. It is analogous to the OBGYN, Neonatologist and Andrologist of human medicine – all combined in a single broad specialization. From antelope to zebras, Theriogenologists work on all species of animals. It is a challenging, unique and rewarding discipline.

I became interested in theriogenology as an undergraduate at Southern Utah University. A professor and mentor named Dan Dail introduced me to this most unique area of veterinary medicine. I learned a lot from him. He entrusted me with a research project looking at the correlation of body condition scores and first service conception rates in heat synchronized beef cattle. His mentorship, along with this research contributed to my acceptance into veterinary school. Dan Dail passed away a few years ago.

At Washington State University, I had the privilege of working extensively with Ahmed Tibary, a world renowned theriogenologist. He has made endless contributions in teaching, published books, chapters and scientific articles. His comparative approach taught me how to think and reason through difficult cases. He also entrusted me with the animals under his care. We published a significant amount of information on reproduction in alpacas. I remember with fondness my time working with him.

My theriogenology work has made me a better veterinarian. My clinical approach has been shaped and molded by the examples of so many mentors and teachers. What drives me is the comparative medicine; that’s what makes my brain move. Whether I am in the clinic working on dogs or cats, or out working with bighorn sheep, elk, alpacas or water buffalo, I am doing what I love.

It is my privilege to serve as the immediate past president of this organization. Upon a cabinet in the lobby of Mountain West Animal Hospital, a small statue sits. The statue depicts a bull named Nandi, the Hindu god of fertility. I am humbled to see my name on the plaque beneath the statue.

Kindness is a commonality among veterinarians who are reproductive specialists. They are approachable and humble. In a profession where arrogance often is the norm, they are a refreshing example of the best of the best. They are among the leadership at nearly every veterinary school in North America. They are leaving a lasting impression on the profession.

I am so proud to be a member of this group.

It has been a tremendous honor for me to serve as immediate-past president of this organization this year.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

The Red Handkerchief

My Take Tuesday: The Red Handkerchief