My Take Tuesday: Veterinary Technician Appreciation Week

Being in the veterinary industry is hard work. Each day brings its share of ups and downs, happiness and heartbreak, and moments where life and death hang in the balance. By the end of the day, we’re often exhausted—physically and emotionally drained.

Since our patients can’t speak for themselves, much of our work involves communicating with their human families. In many ways, we treat the owners as much as we treat the pets. Doing this well requires a rare blend of empathy, patience, and professionalism.

Behind every good veterinarian stands a team of dedicated, compassionate individuals committed to helping people help their pets. I’m fortunate to be surrounded by an exceptional team of veterinary technicians here at Mountain West Animal Hospital.

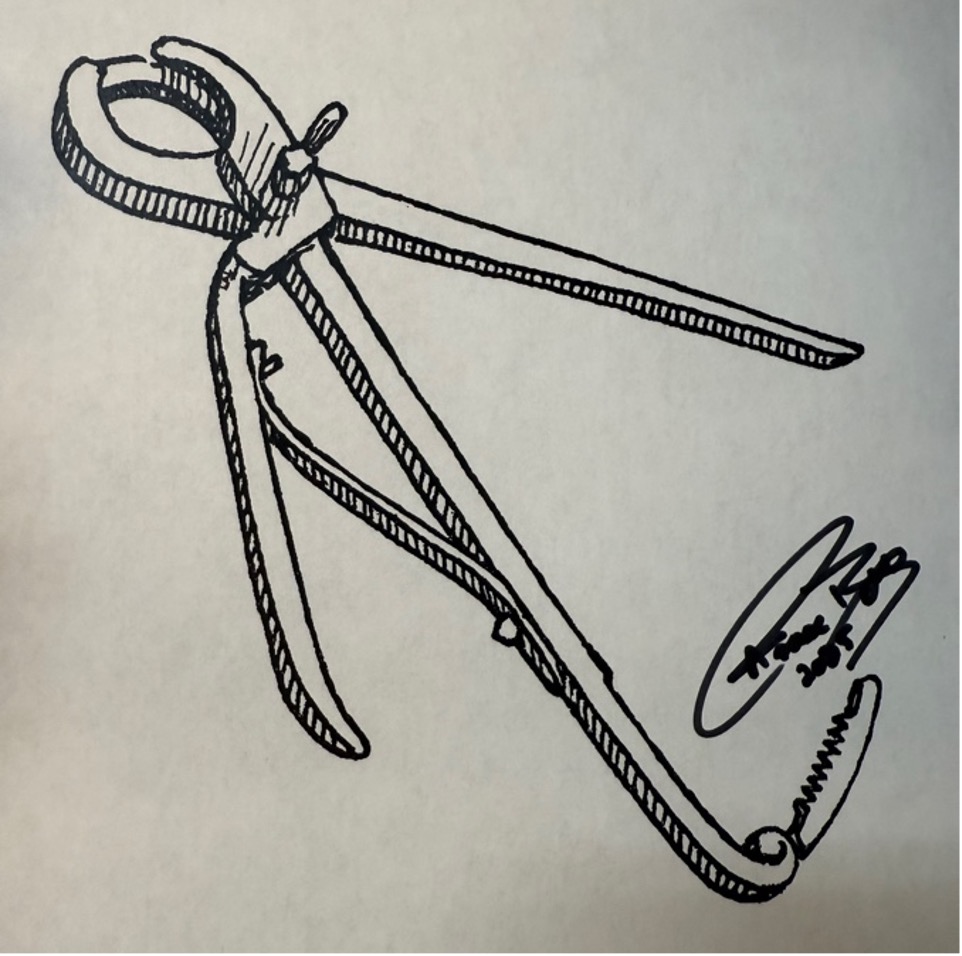

If you’ve ever faced a pet emergency, you know how meaningful it is to have a knowledgeable and caring technician by your side. Veterinary technicians are the unsung heroes of the veterinary world. Without these devoted professionals, our hospital would be a sea of chaos. They do it all—greeting clients, answering phones, restraining animals, drawing blood, assisting in surgery, cleaning cages, and comforting both pets and people alike.

I couldn’t make it through a single day without my team. They bring the skill, heart, and steady hands that make our clinic what it is.

What most people don’t see are the emotional costs of this profession. They don’t see the quiet tears after we’ve said goodbye to a patient we’ve cared for during many years. They don’t see the long hours, the late-night emergencies, or the emotional whiplash of losing one patient and saving another within minutes. They don’t see the neglected pets we try to rehabilitate—or the physical toll this work takes: the bites, scratches, sore muscles, and aching backs.

They don’t see the blood, vomit, and messes that get cleaned up without hesitation, or the moments of triumph when a dying pet turns a corner and walks out our doors, tail wagging, ready to live more good years.

There are heroes among us who never stand in the spotlight, never hear applause, and rarely receive the recognition they deserve.

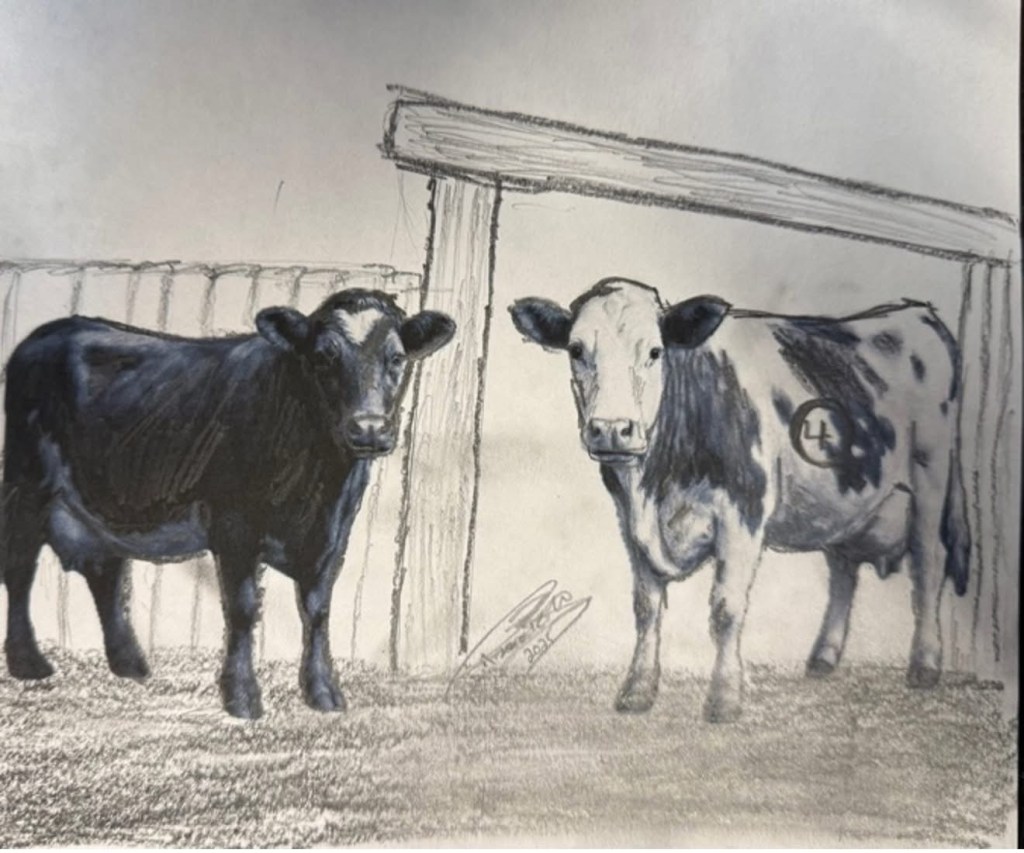

Pictured here are some of my heroes. They are my right hand and my left. They work in a high-stress environment, put in long hours, and face risks every day—all because they care. They care deeply for our clients and their four-legged family members.

This week is National Veterinary Technician Appreciation Week. Please join me in thanking these amazing women for the extraordinary work they do at Mountain West Animal Hospital.

They are, quite simply, incredible.

And that’s my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM