If you attended elementary school with me, you will probably remember my obsession with chickens. As a child, I would draw chickens as I sat at my school desk. Given the many drawing projects that elementary age children have, I drew hundreds of mediocre pictures of my pet chickens. Fortunately, my teachers were patient and supportive. Although my artistic abilities left much to be desired, I was free to draw to my hearts content.

We would receive an annual catalog from Murray McMurray Hatchery. This catalog would depict every conceivable breed of chicken and give a short description of the desirable traits each possessed: comb type, leg feathering, silky, frizzle, bantam, standard, etc. I would spend hours and hours looking through this catalog. Each year, I was allowed to choose a single baby chick of the breed of my choosing. I took this choice seriously.

There are a range of things that one needs to consider when deciding what breed of chicken to have. These include the climate in which you live, whether you are raising backyard chickens for eggs or meat production, their temperament, foraging capability, predator awareness, and broodiness. I meticulously studied each breed and made my selection each year.

Here in the United States, the postal system accepts boxes filled with day-old chicks and delivers them coast to coast with overnight delivery. The chicks travel by Priority Mail and often have no food or water in their cardboard carrier to sustain them. How can this happen? Just prior to hatching, a chick absorbs all the remaining nutrients from within its egg. With this nourishment, the chick can survive for up to three days without food or water. This makes it possible to ship them by mail. In the nest, this process allows the mother to wait for the hatching of other chicks in her clutch before tending to the early hatchers: If chicks required immediate attention, the mother would leave with those that hatched first and the unhatched chicks would perish. This is a fascinating adaptation!

Like humans, chickens have full color vision, and are able to perceive red, green and blue light.

Several studies on visual cognition and spatial orientation in chickens (including young chicks) demonstrate that they are capable of such visual feats as completion of visual occlusion, biological motion perception, and object and spatial (even geometric) representations. One of the cognitive capacities most extensively explored in this domain is object permanence, that is, the ability to understand that something exists even when out of sight.

Other recent scientific studies tell us that chickens recognize over 100 individual faces even after several months of separation. They also confirm that chickens consider the future and practice self-restraint for the benefit of some later reward, something previously believed to be exclusive to humans and other primates. They possess some understanding of numerosity and share some very basic arithmetic capacities with other animals. These findings fascinate me.

To this day, chickens remain my favorite animals. I can sit for hours and watch my flock as they forage and explore the property behind the clinic.

I look back with fondness on the days spent coloring and drawing chickens with crayons.

Memories are painted optimistically with passing years. I miss the worry-free days sitting at a desk in elementary school.

I will forever treasure these pictures and the pleasant memories associated with them.

And that is my take!

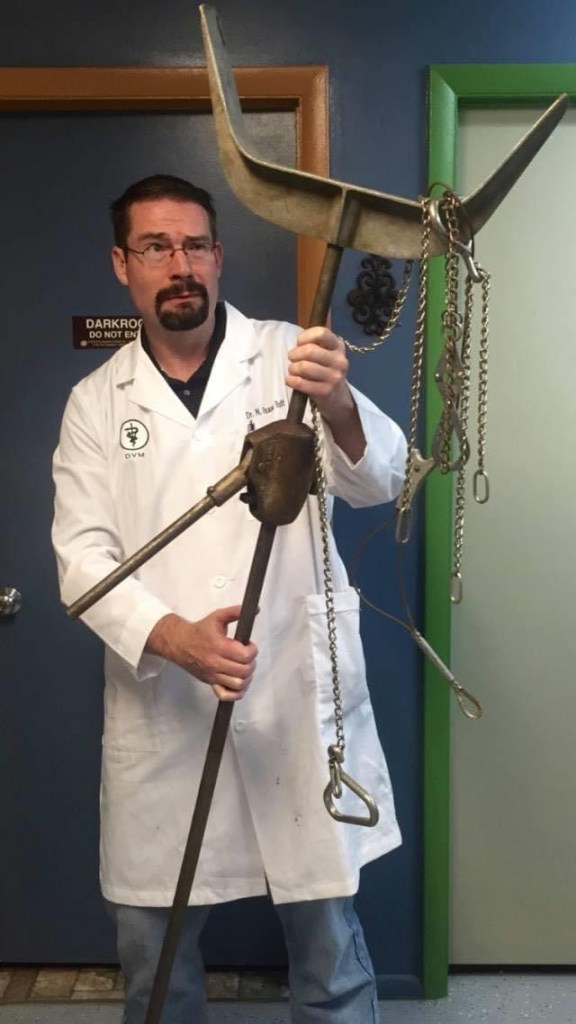

N. Isaac Bott, DVM