My Take Tuesday: The Disgruntled Veterinarian

Veterinarians are some of the most kind and compassionate people on the planet. They are hard workers, and are some of the best people I have ever met.

As with any profession, there are occasional outliers.

When considering the prospect of attending veterinary school, I visited a veterinary clinic, here in Utah County, one day as an undergraduate.

I introduced myself to the veterinarian and asked a little about his experience as a veterinarian. As soon as I began asking questions about which veterinary school to attend, he interrupted me.

“Hey kid, why do you want to be a veterinarian?”, he asked.

I gave the answer I had given so many times. I replied, “Because I love working with animals. I also like working with people and this profession will allow me to help people by helping their animals.”

“What are you? You stupid #%$@>?”, he continued, “What are you going to do when those animals you love bite you and kick you? And what about those people that do not respect you and your expertise and expect you to work miracles? They are far from loyal and they couldn’t care less about you! Get a life kid. This ain’t for you!”

Wow! I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Here was a veterinarian that was clearly dissatisfied with life in general.

After years of grueling work and what he deemed as little professional reciprocity, he had become very cynical. He made it very clear, anyone wanting to be a veterinarian was making a huge mistake. His goal was to dissuade any would be veterinarian that entered the doors of his practice from making the same mistake he did.

To put is delicately, this guy was the east end of a horse facing west.

Looking back, I feel sorry for him. My experience as a veterinarian has been the complete opposite.

The clients I work with are very loyal. My interactions with them are nearly all positive and they love their pets. They follow my recommendations and are always willing to provide the care that their pets need and deserve.

I am glad I did not heed his advice.

Mark Twain eloquently counseled, “Keep away from people who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you, too, can become great.”

I am thankful for those who encouraged me. Who supported me. Who believed in me long before I believed in myself.

Their contributions have led me to where I am today.

And That is My Take

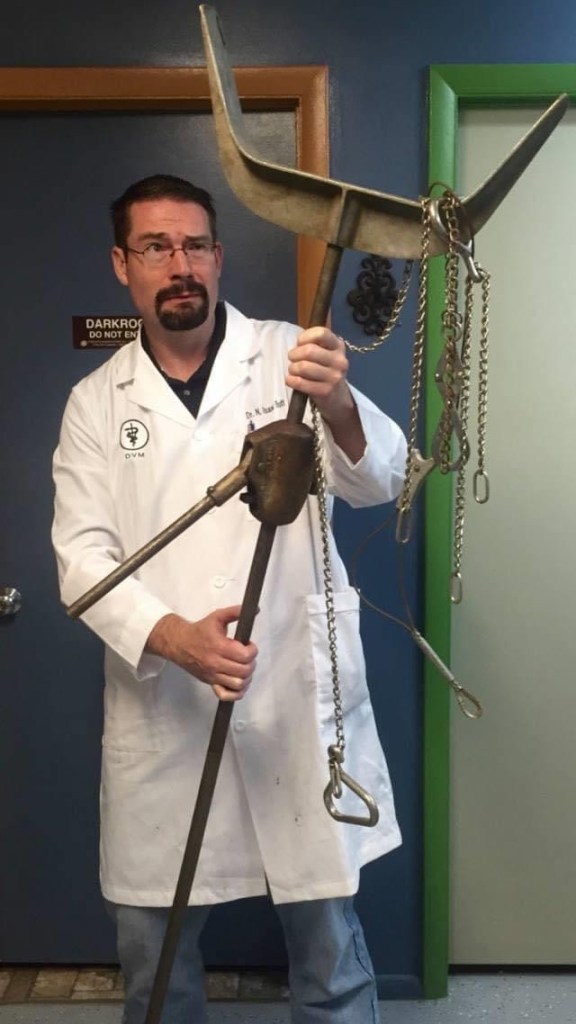

N. Isaac Bott, DVM