It was a beautiful spring morning on the Palouse. The beautiful rolling hills and contrasting colors make this region of the country so unique. As I left my apartment, I took a moment to bask in bright sun of this gorgeous brisk spring morning, permeated with the scent of recent rain. Songbirds filled the air with music that would thrill the greatest maestros, and warblers and finches flashed their dazzling colors in the bushes outside my apartment.

I was an excited 4th year veterinary student just weeks from graduation. As I drove to the veterinary school, I reflected on the past 4 years. A flood of memories entered my mind as I smiled and felt a sense of accomplishment, these were some of the most difficult years of my life and the end was in sight.

This particular weekend, it was my turn to take the emergency call at the veterinary teaching hospital. I had spoken extensively with classmates about what exactly to expect to present throughout the weekend. Each indicated that many dogs and cats would likely present with a variety of ailments. I fully expected to see a variety of routine cases dealing with the perfidious parasites, bothersome bacteria and mysterious maladies that present daily in the life of a veterinarian.

I was not prepared for what was to follow.

Throughout the weekend, a variety of cases presented, none of which were dogs or cats, and none of which I would ever consider routine.

The first case was a hairless rat. This was followed by a parakeet with a broken and bleeding blood feather. A raptor presented with a wing injury and a duck with a fish hook stuck in its bill.

Still another anomaly followed as a boa constrictor presented with a prolapsed cloaca.

At this point in my education, I had virtually no experience with exotic animals. I am terrified of snakes and absolutely did not know the first thing to do with a prolapsed cloaca. I barely knew what a cloaca was!

Fortunately, an exotic animal clinician was a phone call away and she was able to talk me through each case. I learned a lot as I treated each animal and did my best to make each owner and pet comfortable.

Just when I thought I had everything under control, a young woman walked through the front doors of the hospital caring a white box. Small circular 1” holes were cut in each side of the cardboard box.

“I have a chameleon that is sick,” she nervously said with obvious fear and concern in her voice.

I placed my face against the box and peered through one of the small holes. A huge eyeball was all that I could see. Its unflinching stare was somewhat startling.

“He is huge!”, I exclaimed.

“No he isn’t,” she replied, with her voice raising, “He is actually smaller than most.”

“I am sorry,” I replied, “I haven’t ever seen a real chameleon.”

“Oh great, go figure, not only do I have to deal with a student, but I lucked out and got one that clearly doesn’t know what he is doing!” She was clearly upset at this point, as she sighed and shook her head.

Assertiveness has its place, but it is not always a virtue when you are on the receiving end.

“I am sorry,” I began, “Although I am inexperienced, I will call someone that is very competent with chameleons and we will take care of him. I promise I will do my best.”

She seemed to calm down somewhat after this and handed me the white box. I carried the box into the treatment area and immediately opened the lid and peered in. The chameleon stood perched on a branch, clinging with each of its 4 feet. It’s deep green color mimicked the leaves that were placed throughout the box.

I gently removed the little guy and placed him in the glass aquarium type pen used to hospitalize reptilian patients.

Almost immediately, his deep greed color began to fade as he miraculously turned brown, almost identical to the ambience of his new surroundings.

I reached for the phone and dialed the number of the on call exotic expert. I immediately rattled off the details of the case (age, sex, presenting complaint, clinical signs and examination findings). I then explained that I had ZERO experience with this species and that I needed detailed instructions.

Her first question took me off guard.

“Is he pale?” she inquired.

Immediately, I thought to myself, “You’ve got to be kidding me!”

“I am not sure,” I replied. “He was green in his box and then he turned brown when I moved him into the hospital. Now he is looking like a mix of brown and gray.”

“How in the hell can you tell if a chameleon is pale?,” I inquired.

Fortunately, this clinician sensed the frustration in my voice and laughed. She was very patient as she began to explain exactly what I needed to look for.

She talked me through how to administer fluids to a reptile. This is accomplished differently that with other species. Instead of finding a vein and administering the fluids intravenously, they are administered in the common body cavity called the coelomic cavity. I spent the entire night treating this unique patient and monitoring its progress.

Somehow, the chameleon survived. I learned a great deal throughout the remainder of the weekend. Not a single dog or cat ever presented, but I gained confidence and experience with each of the exotic animals that continued to present.

But still to this day, I still have no idea how to tell if a chameleon is pale.

And that is my take!

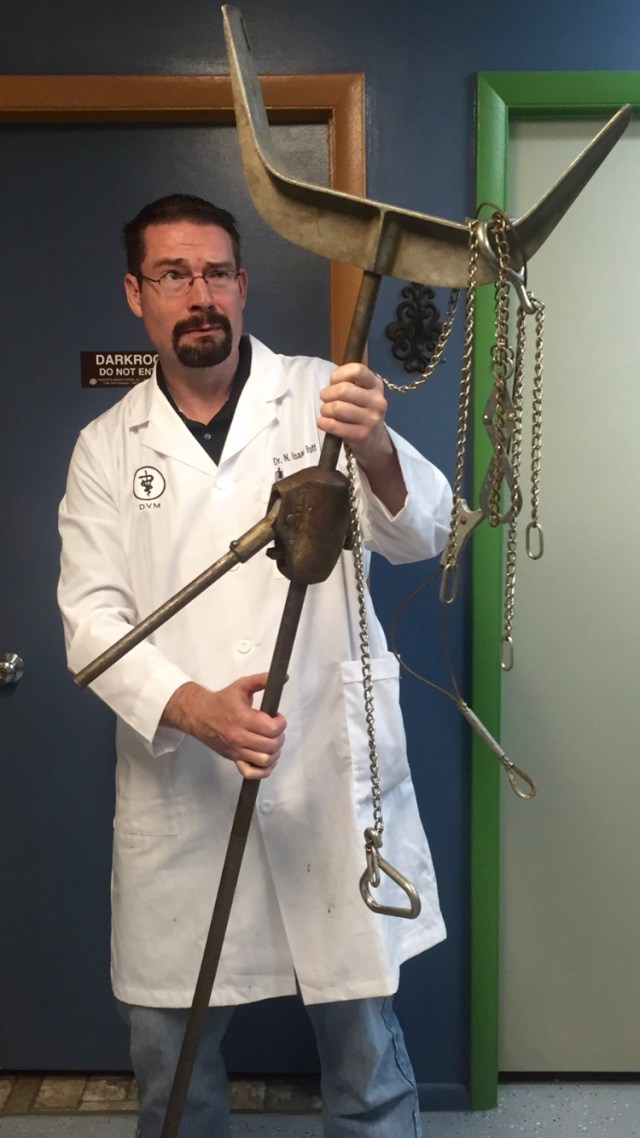

N. Isaac Bott, DVM