My Take Tuesday: Dr. Ruby

My stomach ached. The warm May weather and the beautiful rolling hills of the Palouse were not able to distract me as I nervously opened the letter. As I read the first paragraph, my heart sank.

“You are ranked in the bottom 10% of your class. Statistically, your chances of passing national boards are reduced.”

Tears streamed down my checks as I read each sentence.

It seemed each word stabbed deeper. Each blow, injuring me mortally. Failure. Disappointment. Shame.

Veterinary school was proving to be much more difficult than I had ever anticipated. Many of my classmates had spent years working at veterinary clinics before entering veterinary school. I had spent less than 50 hours shadowing in a veterinary clinic prior to starting veterinary school. Everything I learned during my first year was new to me. It seemed as though I has so much catching up to do.

I knew that I had struggled in a couple of classes, but I did not realize that my ranking fell at the very bottom of the class. The hours and hours of arduous study led to my passing, albeit just barely, of each of my final examinations.

“How could they be so skeptical?,” I silently asked myself as I reread the letter. “Why don’t they believe in me?”

I felt dejected. I felt abandoned. I felt shamed.

“How am I going to recover from this?,” I wondered as I climbed the steps to my second floor apartment.

Fortunately for me, there was someone to meet with. There was someone to talk to.

Dr. Ruby was a pioneer in Veterinary Medicine. Her visionary approach to veterinary medicine education and its inherent professional maladies were years ahead of the rest of the country. She understood the stress that veterinary students faced, and she confronted these difficult situations head-on.

I remember our first meeting as if it were yesterday. I sat on the couch in her office, trembling, as tears poured down my checks. I described how difficult it was for me to prepare for tests. I discussed the issues I faced with each question on multiple choice examinations.

She patiently listened. And then she listened some more.

And then she guided me through some techniques to help with my anxiety. She identified some patterns that prevented me from thinking through the test questions. She provided resources for me to read. She helped me understand that the issues that I faced were normal. She made me feel that I could do better. She believed in me; I could feel it with each appointment.

Miraculously, as the second year of veterinary school started and the examinations started to dot my schedule, my test scores began to rise. With each passing semester, my performance continued to improve.

My confidence increased as I mastered the material in each class.

By the time graduation came, I felt prepared to enter practice. I hit the ground running and have literally not looked back.

Not only did Dr. Ruby believe in me, but she helped me overcome the serious anxieties that come with the rigorous schedule of professional school.

I look back and wonder why that letter was sent to me. Was it meant to inspire? Was it meant to shame? Was it intended to discourage me? What would have happened if I didn’t have anyone like Dr. Ruby to help me through the darkest times? Would I be where I am today?

Failure is inevitable. It creeps up and stumbles even the most skilled on their path to victory. Our response to it’s overreaching nature is largely what determines our potential. As Alexandre Dumas observed, “There is neither happiness nor misery in the world; there is only the comparison of one state with another, nothing more. He who has felt the deepest grief is best able to experience supreme happiness. We must have felt what it is to die… that we may appreciate the enjoyments of life.”

Dr. Ruby has been there for over 2,000 students at WSU over the years. As each class graduates at Washington State University, her influence and vision is passed on to another generation of veterinarians. Her impact is immeasurable. Her legacy is sure. Her vision is cemented in the hearts of those lucky enough to have sat on the couch in her office.

Dr. Ruby is a pioneer. She was one of the first mental health professionals to commit her career to developing wellness programs for the veterinary profession. She has taken on the most difficult challenges facing the veterinary industry. She has educated and counseled thousands of veterinarians about communication skills, stress management, life balance and suicide prevention. She co-founded the Veterinary Leadership Experience, a program that has become the model for veterinary schools around the world. In addition to this, she was also the founding Editor-in-chief of the Veterinary Team Brief, a peer reviewed journal devoted to professional skills. I am not aware of anyone who has given more to the veterinary profession in terms of professional life development, stress management and personal success.

At the end of this month, Dr. Ruby will be retiring. Tears fill my eyes, flowing just as they did on the day I read the letter. I feel so fortunate as I ponder the influence she has had on me. She believed in me when others didn’t. She encouraged me when I felt like a failure.

How much better would we all be if we had a Dr. Ruby to turn to when adversity and failure creep into our lives?

Dr. Ruby inspired me. She encouraged me to rise to my potential. She helped me increase my capacity and helped me be the best I could be. She taught me that I could make a positive contribution to the profession. She helped me believe in myself.

Thank you Dr Ruby. Thank you for believing in me. Thank you for encouraging me when others didn’t. Thank you for your kind and caring counsel. Your influence will forever remain in my heart.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Author: DocBott

Human Blood

My Take Tuesday: Human Blood

Times of severe stress, injury or fear can trigger the reflex: your blood pressure drops, your heart rate slows. This reaction is primeval stuff, buried deep within our brains. Medically, it goes by the name “vasovagal syncope.” Common folk like me simply call it fainting.

Being a veterinarian is not for the faint of heart. On any given day, I will treat a myriad of infirmities. The sight of blood, pus, maggots and trauma are part of a normal day at the clinic. I, fortunately, am not affected by this. I am able to reason and think clearly in situations like this and am able to immediately go about trying to fix the problem. I’ve seen some nasty stuff, but not once have I ever felt light headed with animal blood.

Human blood is a different story. Ironically, I cannot deal with human blood. The sight of it makes me queasy. I have fainted on a couple of occasions at the sight of my own blood. I find it strange that I am fine with animal blood but so unstable when it comes to people.

As luck would have it, on a number of occasions, clients have experienced medical emergencies as I worked on their pets. During one of these situations, I overheard a radio exchange between emergency responders and dispatch.

“He is with a veterinarian,” the dispatcher said.

“Oh good,” the emergency responder replied.

Upon hearing this, I exclaimed, “No, it’s not good! I don’t do human blood! You had better hurry up and get here!”

Keeping it together in such situations is difficult for me. Luckily, no one has died in these situations. However, I did experience a very close call a few years back.

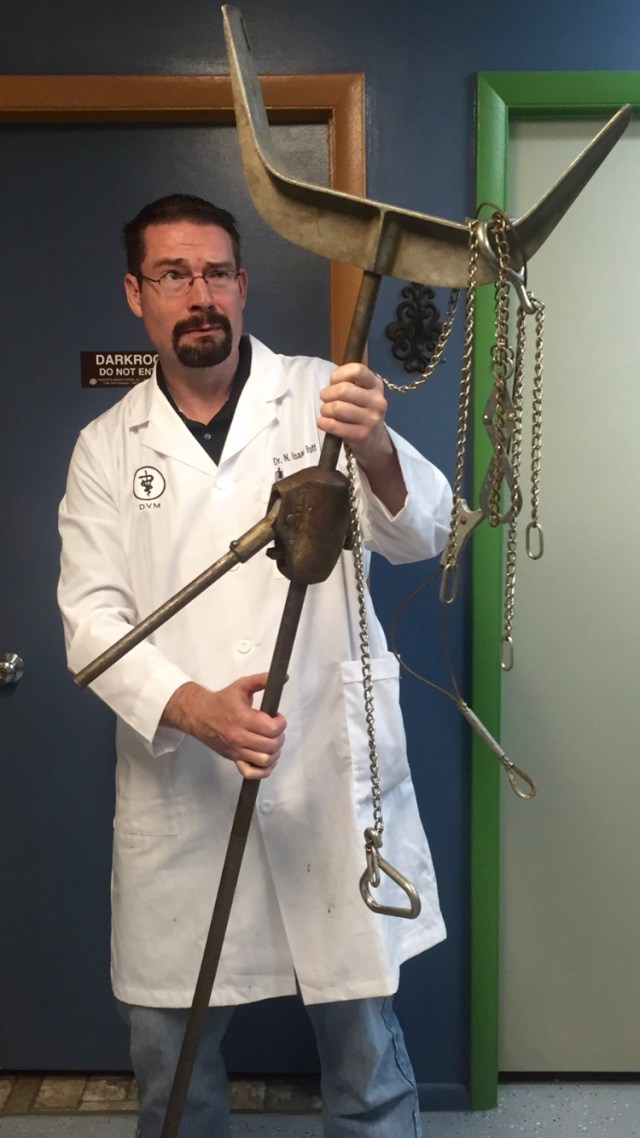

Sheldon was a nice man. His gentle smile and blue eyes were reflective of his kind nature. He raised beautiful Charolais cattle. The pure white bulls he hauled into the clinic on this particular day were no exception. The massive 2000+ pound animals were there to be semen tested before the breeding season.

Sheldon walked with his cane along the side of the alley that led to the squeeze chute. He gently nudged the first bull as I closed the hydronic chute. He opened the side gate and stood directly behind the bull.

I asked about his farm and about the drive down to the clinic. He seemed happy and excited about the coming spring.

As I proceeded to work on the bull, I turned my back to reach for some supplies.

I then asked, “Sheldon, can you help me hold this?”

There was no reply.

“Sheldon,” I continued.

Still no response. I peered into the chute where he was standing just moments before and he was nowhere to be found. As I stood up and entered the side gate, I found Sheldon lying in the alley. His head was lying just inches from the back feet of a bull. Any sudden movements and the bull could easily crush his skull. My blood pressure skyrocketed!

Instinctively, I picked him up and carried him out the side gate. He was non-responsive. I grabbed my stethoscope and listened to his heart. The rate and rhythm were irregular. He was clearly having a heart attack. I shouted for an assistant in the clinic. I asked her to dial 911 and get an ambulance there as soon as possible. I elevated his head and began the first aid I had been taught many times.

I sat with Sheldon until the ambulance arrived. His vitals continued to be irregular, but he continued to breath. As the EMTs arrived, they loaded him in the ambulance. As they pulled out of the clinic, despite having the light on and the sirens blaring, a car nearly side swiped the ambulance.

I stood there in awe. My body trembled as the stress finally caught up. I paced around the parking lot for nearly a half an hour until my nerves were under control and I was able to return to work.

Somehow Sheldon survived the ordeal. I visited him that night in the Payson hospital. He was his normal self as we joked about how bad he had scared me.

He thanked me for helping him.

“It is a good thing you knew what to do,” he continued, “I am lucky you were there.”

If he only knew how uncomfortable I am in situations like this. It took several days for me to be able to return to normal life. The thought of seeing him in the alley with such large animals on either side of him still haunts me to this day.

Fortunately, no other heart attacks have occurred on my watch since that day.

I can quickly fix even the most gruesome lacerations on an animal without a second thought, but when it comes to people, Doc Bott is not the person you want at your side.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

The Disgruntled Veterinarian

My Take Tuesday: The Disgruntled Veterinarian

Veterinarians are some of the most kind and compassionate people on the planet. They are hard workers, and are some of the best people I have ever met.

As with any profession, there are occasional outliers.

When considering the prospect of attending veterinary school, I visited a veterinary clinic one day as an undergraduate.

I introduced my self to the veterinarian and asked a little about his experience as a veterinarian. As soon as I began asking questions about which veterinary school to attend, he interrupted me.

“Hey kid, why do you want to be a veterinarian?”, he asked.

I gave the answer I had given so many times. I replied, “Because I love working with animals. I also like working with people and this profession will allow me to help people by helping their animals.”

“What are you? You stupid #%$@>?”, he continued, “What are you going to do when those animals you love bite you and kick you? And what about those people that do not respect you and your expertise and expect you to work miracles? They are far from loyal and they couldn’t care less about you! Get a life kid. This ain’t for you!”

Wow! I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Here was a veterinarian that was clearly dissatisfied with life in general. After years of grueling work and what he deemed as little professional reciprocity, he had become very cynical. He made it very clear, anyone wanting to be a veterinarian was making a huge mistake. His goal was to dissuade any would be veterinarian that entered the doors of his practice from making the same mistake he did.

To put is delicately, this guy was the south end of a horse facing north.

I feel sorry for him, looking back. My experience as a veterinarian has been the complete opposite.

The clients I work with are very loyal. My interactions with them are nearly all positive and they love their pets. They follow my recommendations and are always willing to provide the care that their pets need and deserve.

I am glad I did not heed his advice.

Mark Twain eloquently counseled, “Keep away from people who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you, too, can become great.”

I am thankful for those who encouraged me. Who supported me. Who believed in me long before I believed in myself.

Their contributions have led me to where I am today.

And That is My Take

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

The Adroit Veterinarian

My Take Tuesday: The Adroit Veterinarian

A few years ago, I had the privilege of visiting a small animal shelter in Cuautla, Mexico. The streets in rural Mexico are full of unclaimed pets. This shelter provides refuge and care for many of these pets.

I will never forget the long car ride. As the rickety old micro-bus careened the dirt roads that led to the shelter, I peered out the window at the green trees and fields that adorned this small piece of heaven. As we passed a small panadería, the familiar sweet smell of bread, churros and pastries filled the air and permeated our senses.

As we arrived at the shelter, a large chainlink fence provided a barrier to the outside world. Inside, lay an expansive series of buildings and kennels. The perfectly manicured lawns provided a sanctuary to hundreds of homeless pets. As I exited the vehicle, I noticed a dog racing excitedly across the grass. It carried behind it a set of training wheels, a custom made wheel chair, that allowed freedom of movement for its paralyzed back legs. I could feel the excitement of this young dog, as it scampered, worry-free across its beautiful sanctuary. I was overcome with a sense of gratitude, and I knew I was standing in a special place.

On this particular day, my assignment was to help spay 10 dogs that were living at the shelter. As I entered the surgery suite, my heart sank. The cement walls were painted dark brown. A single window facing to the north, provided all of the lighting for the room. As I scanned the walls for a light switch, I realized that electricity was a luxury not available in this part of the world.

I remember thinking, “How can I spay these pets without electricity? How can I even see what I am doing? I can’t do this.”

Modern veterinary medicine has changed the face of the profession. Electronic monitoring equipment provides real-time blood pressure, an EKG, oxygen saturation, temperature and allows close monitoring of all vital systems during a surgery. Anesthetic gases, like Isoflurane and Sevoflurane, provide a safe surgical experience and make recovery much less complicated. A surgery room light, a necessary tool, allows visualization of the surgical site and facilitates the entire process.

None of these luxuries were available.

As I prepared to begin surgery, only a single surgery gown was available, and my 6’2” frame far exceeded its size. My large hands could barely fit into the small size 6.5 latex surgical gloves provided. My severe allergy to latex worried me as I pulled the tight gloves over my hands.

The stainless steel surgery table sat low to the ground and could not be adjusted. I had to bend over as I prepared the surgical site. The only surgical monitoring that could be performed was with the use of a simple stethoscope. Injectable drugs were the only available modality to administer general anesthesia.

I took a deep breath. “I can do this,” I reassured myself, “you need to rely on your skills and trust you can do this successfully.”

I nervously began the first incision, as a bead of sweat poured down my forehead.

Each surgery went well. All recovered well without complications.

It is easy to work with the latest in veterinary technology. Digital radiology, surgical monitoring equipment, laser and electrosurgical units provide reliability and safety and are a must in today’s modern practice. I rely on each of them on a daily basis at Mountain West Animal Hospital.

As I left the animal sanctuary, I breathed a sigh a relief. I had learned so much from this experience. It was something that will forever be etched in my memory.

If I were to have to select a single event that has made me the veterinarian I am today, it would be this day in Mexico. I learned to rely on my skill and judgement. I learned that a truly great veterinarian can perform in both a state of the art facility and also in a small cement building without electricity while in a third world setting.

Although the methodology differs, the result remains the same.

I will forever be grateful for this capacitation at a serene sanctuary in a far away place.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

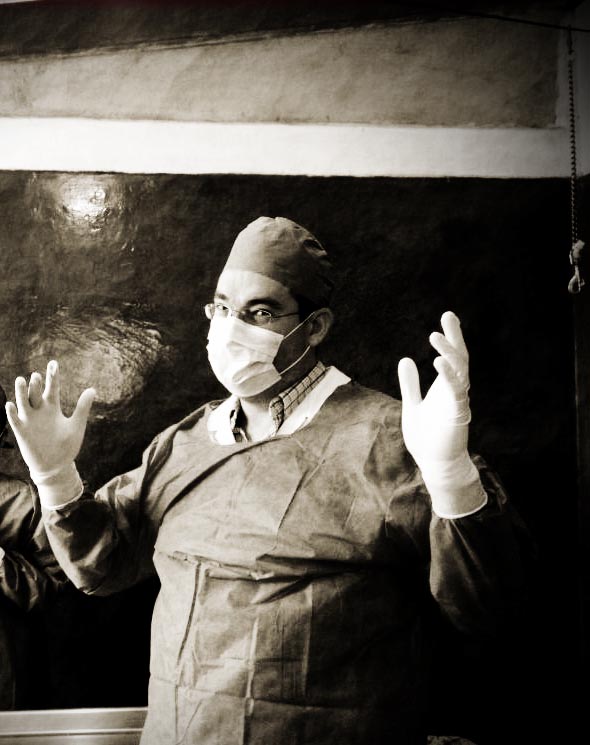

Here I am pictured before the start of the first surgery. Notice the ill-fitting gloves and surgery gown – beneath the surgical mask is a very large, albeit nervous, smile.

Sheep and Stoicism

My Take Tuesday: Sheep and Stoicism

Sheep can be stubborn. I remember as a child trying to herd our small group of ewes to a nearby pasture. Although it was only about a hundred yards away, it didn’t go well. As I turned the sheep out, they all began running in every direction. There was pure chaos. I ended up covered in sheep snot, lying on my back looking up at the blue sky. The sheep were all over town. Not one of them ended up in the desired pasture.

Not long after this, my very wise great uncle, Boyd Bott, taught me an important lesson. The trick was simple: “You can’t herd sheep. You have to lead them.” It is a lesson I will never forget.

Taking a pail of grain and walking out in front of the sheep will yield an opposite response than that described above. The sheep will literally run after you and follow where ever you want them to go. Every time I had to move the sheep from this time forward, it was easy.

Sheep have a strong instinct to follow the sheep in front of them. When one sheep decides to go somewhere, the rest of the flock usually follows, even if it is not a good decision. Humans are the same way. In the bible, sheep are often compared to people. I find this comparison very accurate. We are stubborn. We resist when we are pushed. We follow when we are lead.

There is no better way to learn patience than having a small herd of sheep. They require much attention, protection and care.

Next time you find your patience running thin, think of exercising oversight instead of compulsion. It will most certainly yield a better result.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

This photo is of Dr. Bott holding a newborn lamb on his family farm in 1985.

A Scar

My Take Tuesday: A Scar

You can definitely see it if you look close enough, each time I extend my left hand with my palm down. It runs nearly perpendicular to the axis of my index finger.

Scars are a physical reminder of our own survival. They tell a story about places that you’ve been. They are tangible roadmaps to life’s lessons learned.

Every time I notice the scar on my finger, my mind travels back to my senior year of veterinary school in 2008. My best friends from veterinary school, Dan and Travis, were with me on this wild adventure.

It was a beautiful November day in Emmett, Idaho. The crisp fall air and dark yellow leaves of the cottonwood trees reminded me why this was my favorite time of the year.

During my last year of veterinary school, an entire month was spent at the Caine Veterinary Teaching Center in Caldwell, ID. This provided hands on training in a variety of agricultural species. Our days were spent on massive dairy operations, in the classroom and at livestock auctions.

On this particular day the sale yard was full. Cattle of every breed, gender and size were being sold and sorted through the sale barn.

My tasks were simple: 1) Vaccinate the females between 4-10 months of age. 2) Diagnose pregnancy in adult females. 3) An occasional bull calf would also need to be castrated.

Often cattle are sold because of their disposition. Wild, aggressive and flighty cattle are difficult to handle. Studies have shown a lower pregnancy rate among beef cattle that are flighty. Farmers are quick to cull cows that exhibit these traits. Therefore, wild and crazy cattle are prevalent at a livestock auction. Extreme care must be taken to avoid injury.

Facilities to process cattle make all of the difference for a veterinarian. It is very dangerous to attempt to process cattle in a rickety old squeeze chute. Unfortunately, too many sale barns have cattle handling facilities that leave much to be desired.

A black Angus calf entered the chute. I had castrated many calves before this and was very comfortable with the procedure. To facilitate castration, I entered the squeeze chute behind the calf. I reached down and made an incision. The calf immediately jumped and kicked. His right hind leg hit my right hand with incredible accuracy. The knife, still held securely in my right hand, plunged downward. The blade entered the index finger of my left hand, right between the first and second knuckles. The blade sank deep, and only stopped as it hit the bone in my finger.

The pain was immediate. I quickly exited the chute, holding my left hand tightly. Blood poured down my hand and dropped on the ground. The professor asked, “What happened?”

“I cut myself,” I responded.

As I stepped away from the squeeze chute, I glanced down at my finger. The open wound gushed blood. I immediately became light headed and nearly fainted as I stumbled to the truck.

I wrapped my finger tightly and headed to the nearest urgent care clinic. The throbbing pain seems to peak with each heartbeat.

After a couple hours and a few sutures, I was back at the sale yard. The remainder of the day went smoothly.

I will forever carry a reminder of that November day in Emmett, Idaho. Although time tends to color our memories optimistically, I still remember the painful lesson I learned that day.

Such is life. The ups and downs leave us battered and scarred. But with time, things get better. The pain won’t always be there and someday we will look back at each scrape and scratch and be reminded that scars are beautiful.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

Don’t worry Doc, She’s a tame cow

The Most Difficult Part of My Job

My Take Tuesday: The Most Difficult Part of My Job

Death and dying are uncomfortable subjects. For some, it stirs up painful memories of past losses. For others, it is a reminder of our mortality or the mortality of those we love.

As I tend to the animals in my care, I will lose patients to death despite my best efforts. Often at these times, I am exposed to the emotions of the families who have loved them. For some, there are dramatic outbursts; for others, emotions will be put on hold for private moments.

As different as people are, so are their reactions. No right or wrong. I always try to respect and accept the fact that we all grieve and express grief in our own way and in our own time, and I try my best to be there to support my clients through this most difficult time.

I have to deal with death on a daily basis. Many of these are pets that need to be euthanized. It is among the most difficult aspects of my job. I see the sadness in family members eyes when they have to say good bye to their family member. I often tear up when the strong bond between the family and pet is obvious.

I cannot feel their pain. I did not have the years of interaction with their family member. I didn’t see the unique personality they are talking about. I only have treated this pet on a few occasions and our interactions usually lasted only a few minutes.

What I can show is empathy. My professional familiarity with death means I also know a great deal about grief — my own, of course, and also that of the families whose pets I have looked after throughout their lives.

Dealing with this on a daily basis for many years is difficult. Many veterinarians suffer from severe burnout and fatigue, and sadly a 4x higher suicide rate when compared to the general public.

Veterinarians encounter death frequently, along with some moral issues human doctors never face. Consider the client I need to counsel and help to choose between a costly operation for their pet or paying their mortgage — or worse, a beloved patient I operate on who, despite good care, still dies. Or another case where horrific animal abuse is evident.

When these stresses combine with long working hours and on-call pressures, it’s easy to see how anyone could melt down.

I try to hard to focus on the goodness of people who save animals, instead of the evil of those who hurt them. This helps tremendously. I count myself so fortunate to have the clients that I do. They are loyal and caring. They are kind. I take the trust they have in me very seriously and I do my best every day to be the very best veterinarian I can be.

The loss of a pet should not be taken lightly and it is not something most people get over quickly or easily – although many may think there is a social stigma not to grieve for animals as we do for humans. The fact is that the bond that is formed between people and their pets is in many cases even stronger than some of the bonds between people.

Although I do not fully understand the love you have for your pet, I do care about your feelings and try my best to show this with each interaction I have. This is particularly true when dealing with these difficult end of life decisions. If you have had to go trough this, my heart aches for you.

Losing a pet is tough. I mourn your loss.

I also strongly believe that the bond between human and animal continues, across the rainbow bridge, between this life and the next.

And That is My Take

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

The Tale of the Tail

My Take Tuesday: The Tale of the Tail

While growing up on a small farm in Castle Dale, my usual day began at 5:00 AM. My family owned 2 Guernsey milk cows. Their names were Mahana and Mokey. Dairy cows are milked either two or three times a day on most dairy farms. We elected the twice daily milkings which we spaced out evenly in a 24 hour time frame. My older brother and I would take turns milking each of them. I would milk Mahana in the morning and Mokey in the evening.

Although born as twins, each cow had distinct capricious personalities. Dealing with Mokey was a roll of the dice. She was unpredictable and instantly agitated. She was able to place a forward kick from her rear right leg precisely in the milk bucket or the center of my shin as she desired. Her eyes bulged out the side of her head, she always had a wild look and seemed to be able to track every move I made before it happened.

Mahana was docile and aware of her surrounding at all times, she could transition from tranquility to rage in a split second. She seemed to be swooshing her tail constantly. Her tail would connect against the side of my face. Although frequent bombardment from flies would initiate this torture, she quickly learned that her tail was a weapon capable of inflicting pain and discomfort. She would constantly whip my face with the coarse hairs at the end of her tail, which was analogous to a lashing from a bullwhip. Accumulations of feces and mud made on the distal end of her normally soft tail hair would transform her tail into a rigid and most dangerous weapon. After enduring this month after month, I decided that it was time to do something about it. The tail needed to be controlled and contained… But how?

Tail docking was out of the question, although an inconvenience for me, her tail was important for her, particularly during the warm months of summer when flies and other biting insects abound.

My first idea was to shave the dangerous hair off the end of the tail. This would clearly remove the most painful part of the ordeal. I used an old pair of electric clippers and shaved the tail.

That afternoon, I sat down on the milking stool and began the normal routine, assuming my intervention would be successful. Almost immediately, her tail came flying towards me. Unable to duck out of the way I just leaned into it. The shaved tail landed across my cheek and left a large welt. It felt like I had been slapped with a stiff garden hose. The pain was considerably greater than that caused by the tail hair. I realized that I had unknowingly created an even more formidable weapon.

My second idea was to develop an anchor to which I would tie the tail. This would prohibit the tail from reaching my face. I searched for an object to which I could anchor her tail to. I found a cinderblock that seemed to fit the part.

Having been a boy scout for years, I knew how to tie a good knot. I used orange bailing twine to tie the secure knots connecting the tail to the cinderblock anchor. There was no way the knot was going to come undone.

Many may wonder just how strong a cow’s tail really is. How much weight can it lift? Well, that day I learned a painful lesson, and I can attest that a cow’s tail can indeed easily lift and swing a cinderblock.

The solution to the problem was simply anchoring the tail to the back leg of the cow. Ironically, it took a cinder block to lead my simple mind to the even simpler solution.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

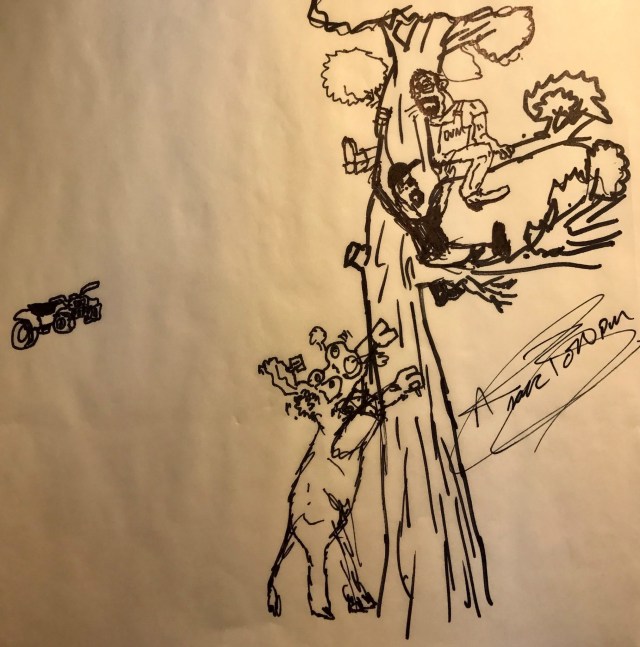

Up A Tree

My Take Tuesday: Up A Tree

In the early spring, when the ice and snow begin to disappear, most of the fields in Utah County are a muddy disgusting mess. A farmer would be wise to avoid calving their cattle during this time. A clean environment required for calving is impossible to find in a swampy, muddy field.

Dwane is not a typical farmer. To him, this is the perfect time of year for calving. His solution to the muddy disgusting mess in his pasture was simple: A four wheeler.

Each morning he would ride around the cow pasture to check on his pregnant stock. On this particular day, had spotted one cow calving and could see the infant’s nose and one foot exposed. Circumstances such as this require help from DocBott.

“Hey Doc, I need some help with one of my cows,” Dwane stated matter-of-factly, “She is kind of a wild one, so I don’t dare work on her by myself.”

I know better than to get myself into a situation like this. There is no way it can end well. Unfortunately, as it often goes, I gave in and headed towards Dwane’s place in Palmyra.

Dwane sat, on his Honda four wheeler at the gate. Every inch of the machine was covered in dark brown mud. As I looked into the field, I could see a few cows standing literally knee deep in mud.

“What a mess!”, I exclaimed, “Dwane, you really need to get a barn if you are going to calve out this time of year.”

“Yeah, I know,” he replied, “But you know how beef prices are this year.”

He did have a point, unpredictable and forceful influences that have negligible affect on most businesses, can dramatically alter the beef industry. From changing product demand, rising input costs and market fluctuations, to weather patterns and even consumer nutrition and lifestyle trends, farmers and ranchers must balance a long list of variables in order to be successful. The beef industry is not for the faint of heart.

“Where is she?,” I asked.

“Hop on, Doc, I will take you to her”

Out in the center of the field, along side a large cottonwood tree, the big Angus cow was comfortably sitting. As we approached her on the four wheeler, the wide eyed cow jumped up on her feet. Almost instantly, out popped the calf.

“Wow!” Dwane explained, that was easier than I thought it would be.

“It sure was,” I replied.

We should have just kept driving on the four wheeler at this point. The mother and newborn were both apparently healthy. There was no reason to stay, except that Dwane felt this was an opportune time to put a tag in the calf’s ear while we were near.

We dismounted and quietly approached the new born calf. Dwane reached down and quickly placed the tag in the left ear of the calf. The small calf let out a quiet but deliberate “moooooo”.

No sooner had the calf opened its mouth, the cow charged. She hit Dwane squarely in the chest. He immediately flew backwards towards the tree. He quickly jumped up and raced behind the tree, trying to use its massive trunk as a shield from the raging bovine.

I raced behind the tree as she bellowed and snorted. I looked at Dwane and he looked at me. We both knew there was only one way out – and that was up! We both climbed as fast as we could. Our mud covered rubber boots slid as we tried to climb the massive tree.

A large low hanging branch provided support as we held on and climbed on top of the life saving perch.

“Are you ok?” I asked

“Yeah,” Dwane replied between gasps, “I thought we were both dead!”

“Me too!” I agreed.

Fortunately, we have cell phones in today’s world, if not for that, Dwane and I would have had to stay in the tree for who knows how long.

“Just look for a four wheeler and a savage cow circling a tree,” I heard Dwane say as he grinned.

As we rode out of the pasture, he commented, “Hey Doc, I think I just might get that barn after all.”

“That sounds like a great idea,” I agreed, “I ain’t much of a tree climber!”

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM