My Take Tuesday: The Adroit Veterinarian

A few years ago, I had the privilege of visiting a small animal shelter in Cuautla, Mexico. The streets in rural Mexico are full of unclaimed pets. This shelter provides refuge and care for many of these pets.

I will never forget the long car ride. As the rickety old micro-bus careened the dirt roads that led to the shelter, I peered out the window at the green trees and fields that adorned this small piece of heaven. As we passed a small panadería, the familiar sweet smell of bread, churros and pastries filled the air and permeated our senses.

As we arrived at the shelter, a large chainlink fence provided a barrier to the outside world. Inside, lay an expansive series of buildings and kennels. The perfectly manicured lawns provided a sanctuary to hundreds of homeless pets. As I exited the vehicle, I noticed a dog racing excitedly across the grass. It carried behind it a set of training wheels, a custom made wheel chair, that allowed freedom of movement for its paralyzed back legs. I could feel the excitement of this young dog, as it scampered, worry-free across its beautiful sanctuary. I was overcome with a sense of gratitude, and I knew I was standing in a special place.

On this particular day, my assignment was to help spay 10 dogs that were living at the shelter. As I entered the surgery suite, my heart sank. The cement walls were painted dark brown. A single window facing to the north, provided all of the lighting for the room. As I scanned the walls for a light switch, I realized that electricity was a luxury not available in this part of the world.

I remember thinking, “How can I spay these pets without electricity? How can I even see what I am doing? I can’t do this.”

Modern veterinary medicine has changed the face of the profession. Electronic monitoring equipment provides real-time blood pressure, an EKG, oxygen saturation, temperature and allows close monitoring of all vital systems during a surgery. Anesthetic gases, like Isoflurane and Sevoflurane, provide a safe surgical experience and make recovery much less complicated. A surgery room light, a necessary tool, allows visualization of the surgical site and facilitates the entire process.

None of these luxuries were available.

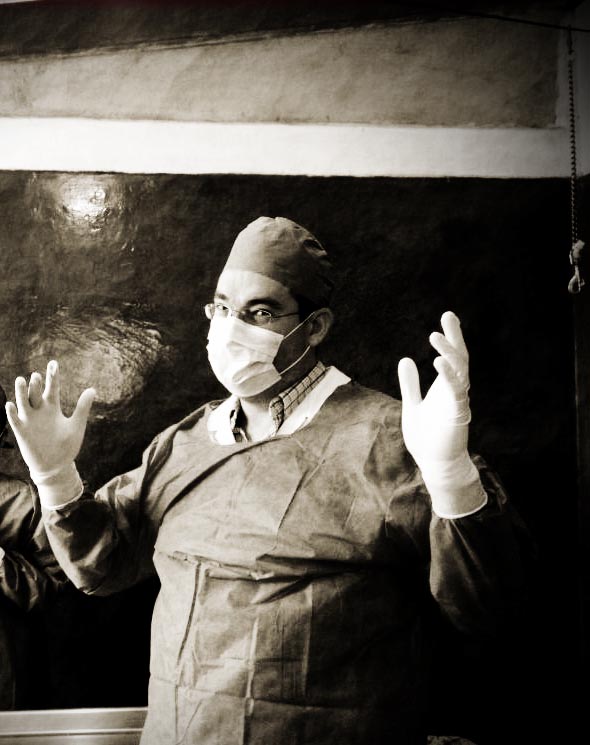

As I prepared to begin surgery, only a single surgery gown was available, and my 6’2” frame far exceeded its size. My large hands could barely fit into the small size 6.5 latex surgical gloves provided. My severe allergy to latex worried me as I pulled the tight gloves over my hands.

The stainless steel surgery table sat low to the ground and could not be adjusted. I had to bend over as I prepared the surgical site. The only surgical monitoring that could be performed was with the use of a simple stethoscope. Injectable drugs were the only available modality to administer general anesthesia.

I took a deep breath. “I can do this,” I reassured myself, “you need to rely on your skills and trust you can do this successfully.”

I nervously began the first incision, as a bead of sweat poured down my forehead.

Each surgery went well. All recovered well without complications.

It is easy to work with the latest in veterinary technology. Digital radiology, surgical monitoring equipment, laser and electrosurgical units provide reliability and safety and are a must in today’s modern practice. I rely on each of them on a daily basis at Mountain West Animal Hospital.

As I left the animal sanctuary, I breathed a sigh a relief. I had learned so much from this experience. It was something that will forever be etched in my memory.

If I were to have to select a single event that has made me the veterinarian I am today, it would be this day in Mexico. I learned to rely on my skill and judgement. I learned that a truly great veterinarian can perform in both a state of the art facility and also in a small cement building without electricity while in a third world setting.

Although the methodology differed, the result remains the same.

I will forever be grateful for this capacitation at a serene sanctuary in a far away place.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM

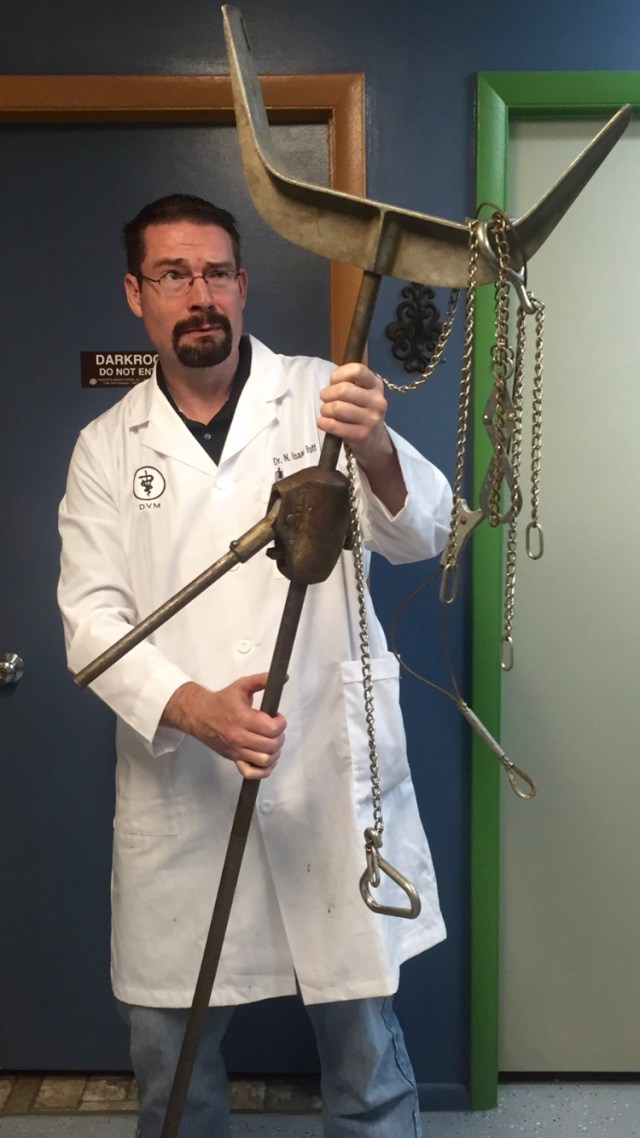

Here I am pictured before the start of the first surgery. Notice the ill-fitting gloves and surgery gown – beneath the surgical mask is a very large, albeit nervous, smile.

My Take Tuesday: Allergies – The Itch Is On!

My Take Tuesday: Allergies – The Itch Is On!