Sunday Stanza: Castle Dale

Where the San Rafael whispers to cottonwood trees,

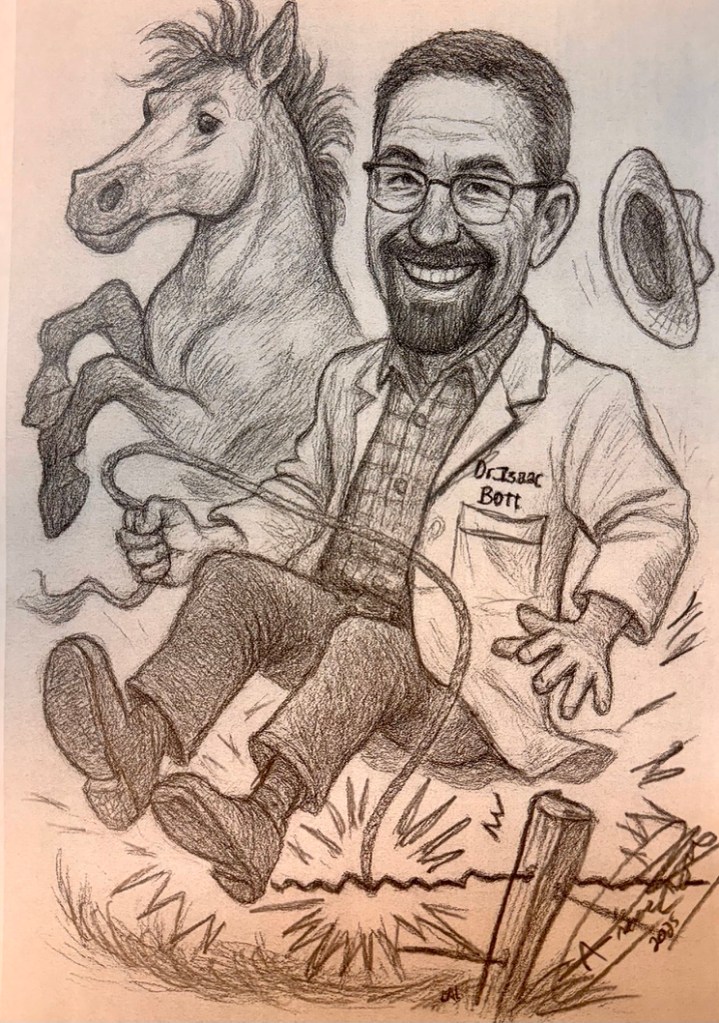

DocBott

And the wind hums tales on a warm desert breeze,

Lies a town built on shell and an honest day’s sweat—

A place that remembers, a place won’t forget.

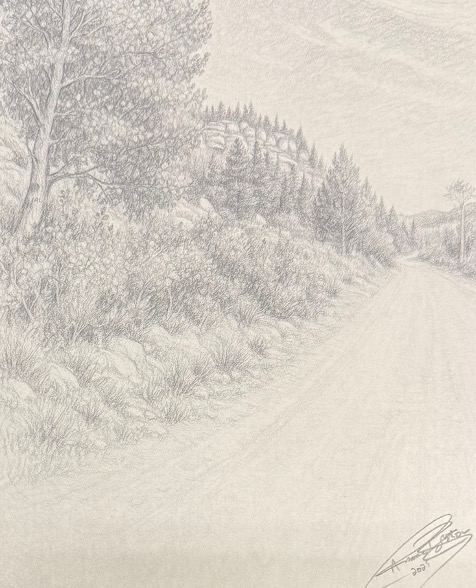

The Wasatch Plateau stands watch in the western sky,

Snow-capped in winter, come summer, bone-dry.

Its majestic ridges catch sunsets in lavender flame,

While Cottonwood Creek gentle echoes Castle Dale’s name.

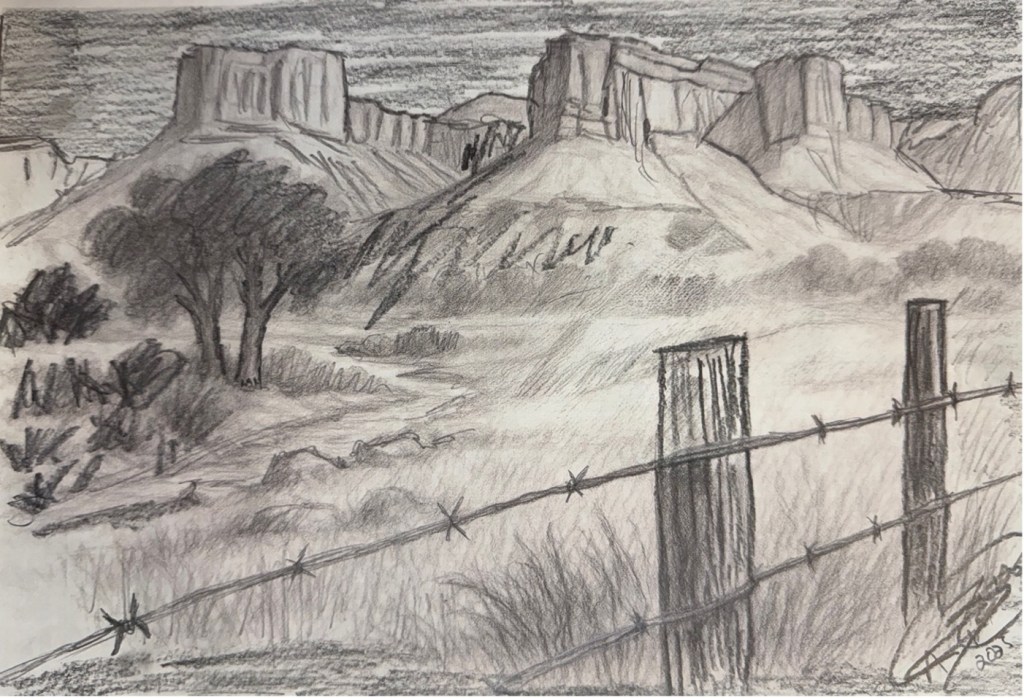

The cliffs rise like castles, in rust-red and gold,

Time-chiseled by silence, majestic and bold.

Juniper clings to the hillsides like kin,

Rooted in rock, defying the wind.

The fields are a patchwork of alfalfa and hay,

And tractors still rumble at the close of the day.

The scent of sagebrush and dry diesel smoke

Is better than perfume for Castle Dale folk.

Cottonwood Creek snakes like a sidewinder’s trail,

Just shy of defiant and too tough to fail.

It waters the cottonwoods and willows patches lazy and slow—

And teaches young kids where the rainbow trout won’t go.

The Main Street’s a page from a bygone day,

Where the post office gossip still makes its own hay.

You wave at each truck, though you might not know Jack—

But you nod just the same with a tip of your hat.

Horses still graze near the old power line,

And cattle still bellow at around quarter-past nine.

Fences lean slightly, but still do their part,

Like the people who built them—with grit and with heart.

Now I’ve seen some high places and traveled a spell,

But none quite so grounded or humble as well.

For all of life’s lessons and truths tried and true—

Castle Dale taught me most of the ones that I knew.

So, if you should wander, just slow your ol’ trot,

You’ll know you’ve arrived at the end of a thought.

Where the stars still remember each cowboy and tale—

And the Creator carved a monument and named it Castle Dale.

At dusk, when the sun dips its hat to the west,

And the stars settle in for a long evening rest,

The silence says more than a thousand loud cheers—

This town’s carved in clay and etched in my years.

Now, if Heaven’s got sagebrush, blue clay, and cows,

And fences that lean like the ones in this town,

If the sun takes its sweet time settling down,

Then Heaven’s just west of this small little town.