My Take Tuesday: Fleming’s Vest-Pocket Veterinary Adviser

The year was 1904. The town of Emery, Utah had a population of around 560 people, nearly double what it has today. Emery has always been an agricultural community. Ranching and farming are as much a part of its scenery as the towering cliffs that overlook the small town. Visitors are often taken aback by the beauty and expanse of this beautiful country on the edge of the San Rafael Swell.

Lewis W. Peterson made his living as a farmer. Life during this time could not have been easy. Lewis and his young wife experienced extreme heartbreak during their first few years together. Their only two children at the time would die from an influenza outbreak that indiscriminately killed so many in this small community in 1907.

The remote location of the town isolated it somewhat from other communities. The town had a fine yellow church house that had a large ballroom floor that served not only for Sunday worship services, but also for social gatherings. This building still stands in the center of town today.

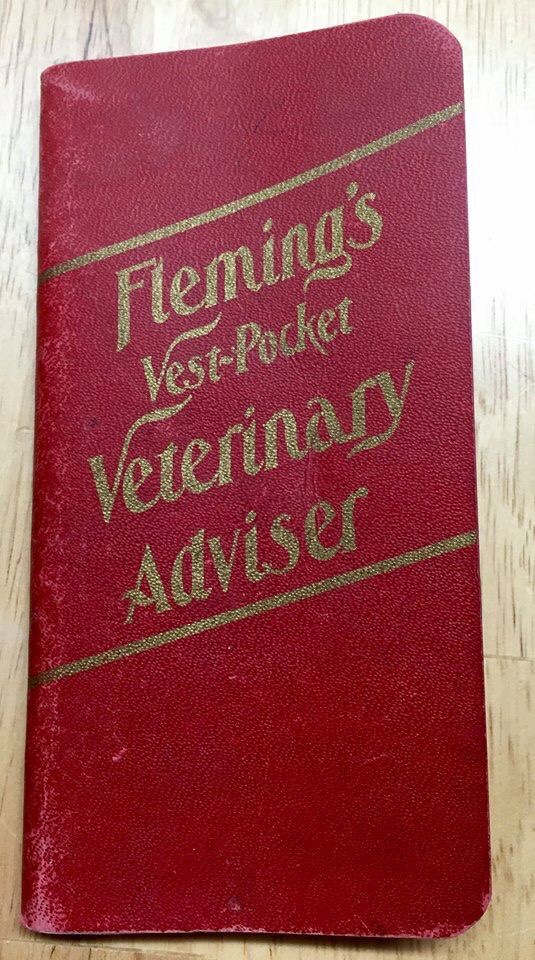

Information came in the form of newspapers and books. Knowledge was a valuable asset that would set certain farmers apart. When information was available, these farmers were open to reading and learning. It was during this time that LW Peterson acquired a new book called, Fleming’s Vest-Pocket Veterinary Adviser.

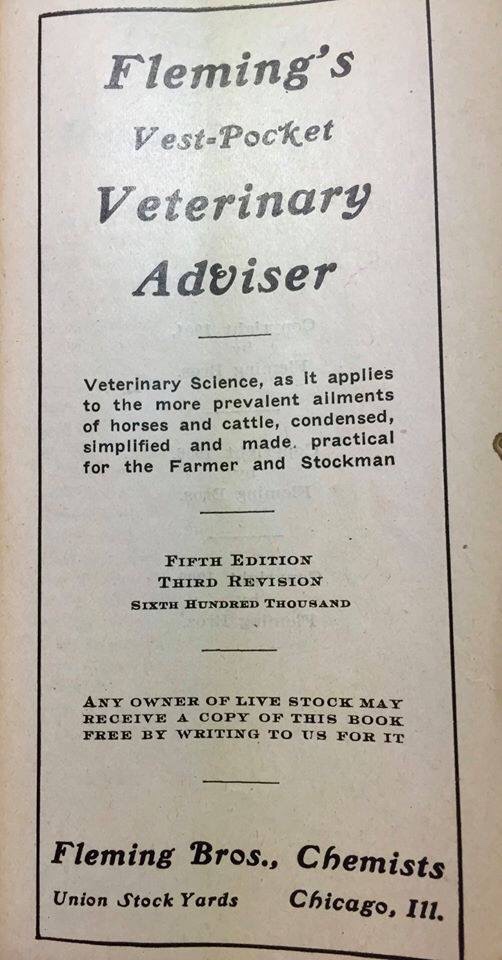

This now 114 year old, pocket size handbook of veterinary information pertained to diseases of horses and cattle, and was designed to help farmers and stockman. It provided 192 pages of everything from birth to aging, to caring for illnesses, to poisonous weeds, maintenance, how to feed, and recipes for concoctions to treat a variety of ailments.

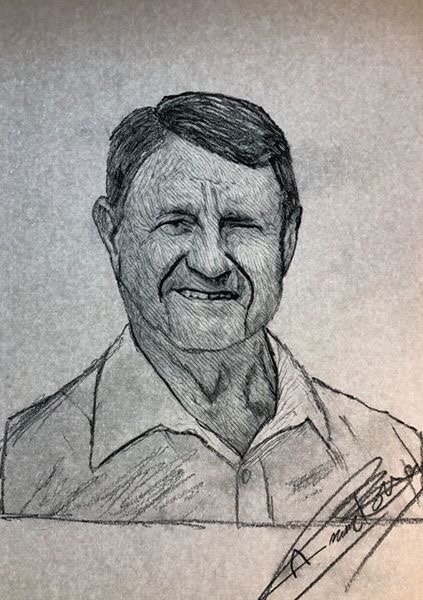

This book must have helped LW. He kept the book. He passed it down to his son, Kenneth Peterson, who passed it to his son Hugh Peterson.

My grandfather, Hugh Peterson, gave it to my mother, who gave it to me. This book is displayed prominently in the museum case in the reception area of Mountain West Animal Hospital.

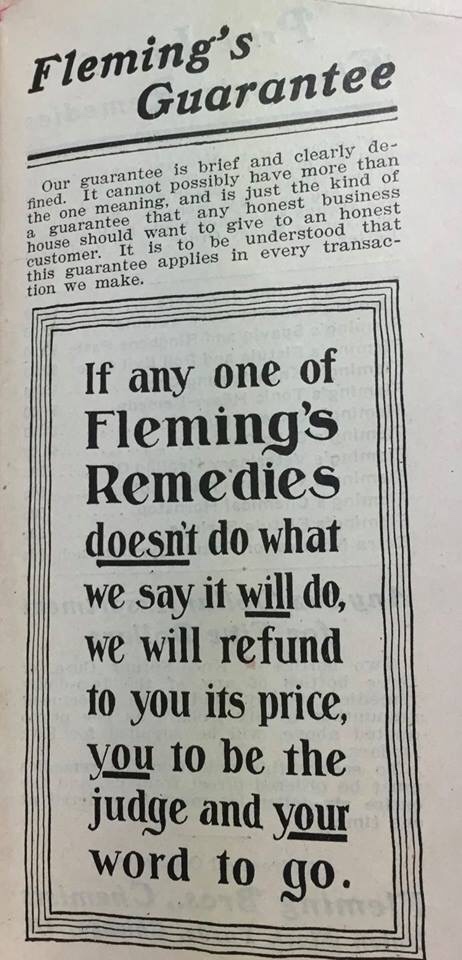

The well worn pages of this book are fascinating to read through. Although veterinary science was in its infancy at this time, it is still interesting to read about treatments used. Without the luxuries of modern antibiotics, antiseptics, anesthetics and anti-inflammatories, these treatments were innovative for their time. The early 1900’s provided incredible advances in hygiene practices, preventive medicine concepts evolved, the first vaccines appeared, nutrition was studied and research was beginning to show which therapeutics actually worked, and why.

Perhaps some would consider this dated literature obsolete. Much of the information contained therein certainly would be considered so. I, however, consider it a treasure. I wonder if LW realized that, more than 60 years after his death, a veterinarian, carrying 1/16th of his DNA, would appreciate this book passed from generation to generation.

I will keep this book safe and pass it on to my children. Who knows, perhaps in another 100 years, it will still be seen as a valuable piece of family and veterinary history.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM