My Take Tuesday: Frank The Turtle

Third grade seemed to be a particularly creative time during my childhood. I remember sitting quietly in Mrs. Wikersham’s class at Castle Dale Elementary. As part of our routine, we would recite a poem each day. Most of the poems were short and simple and easy to remember. I still remember most of them verbatim. One of my favorites was about a little turtle, and it went like this:

“There was a little turtle.

He lived in a box.

He swam in a puddle.

He climbed on the rocks.

He snapped at a mosquito.

He snapped at a flea.

He snapped at a minnow.

And he snapped at me.

He caught the mosquito.

He caught the flea.

He caught the minnow.

But he didn’t catch me!”

I remember Mrs. Wikersham’s facial expressions vividly as she would teach us hand actions that went along with this poem.

A snapping turtle? It was something I could only dream about as a sheltered kid in a small town.

I recently thought about Mrs. Wikersham’s class after receiving an unusual call.

Frank the turtle needed an examination and a health certificate before flying to a warmer state. His owner called and explained that she could not find a veterinarian that would look at her turtle before her afternoon flight.

I really don’t know much about exotic pets, I somewhat reluctantly agreed to see her and provide the needed travel paperwork.

I entered the exam room to see the cutest little turtle imaginable. His innocent eyes peered up at me as I held him in my hands. I quickly looked him over and filled out the needed paperwork.

I handed the paperwork to the client and wished her safe travels. I then reached down to pat Frank on the top of his shell. Without warning, Frank snapped the tip of my right pointer finger.

Immediately, pain shot up my hand and continued all the way up my arm.

“Ouch!!!” I exclaimed, “That really hurts!”

Bewilderment filled my eyes. I didn’t see this coming. Frank, it turns out isn’t quite as sweet as he appears.

He might have snapped at that mosquito and caught that flea,

But in the end, Frank the turtle also caught me!

And that is my take!

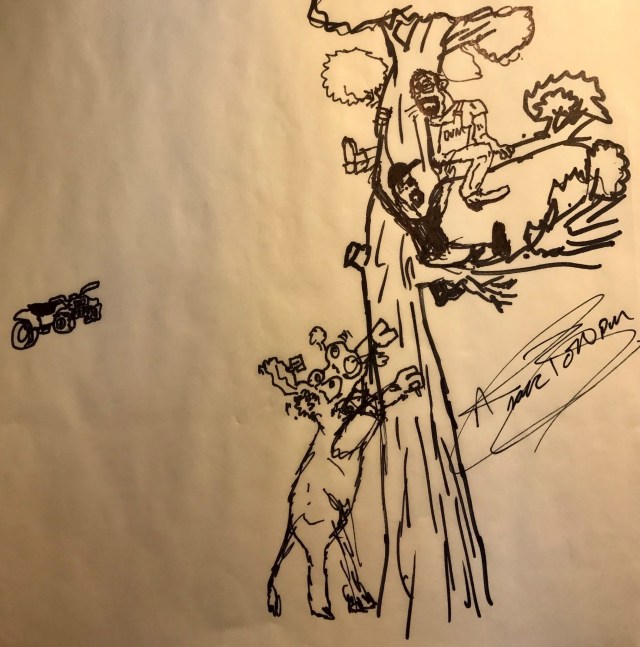

N. Isaac Bott, DVM