My Take Tuesday: The Fragility of Life

Just west of Castle Dale, Utah, the sky above Horn Mountain turns a beautiful cinnamon on clear summer nights as the sun sets over the place I call home. These summer nights smell of freshly cut grass and alfalfa, of sagebrush and lilacs.

If you are heading west along Bott Lane, just past the tall poplar trees, lies a piece of ground that was homesteaded by my great-great grandfather. This piece of land has passed from generation to generation, from fathers to sons, and has always remained in my family.

On the east side of this piece of land, a silhouette of a Ford Tractor and a Hesston Hydroswing Swather were visible on many beautiful summer evenings during my childhood. On the tractor, sat my uncle Jerry Bott.

Jerry was a giant of a man. He stood over 6’4”. His gentle demeanor and kind heart were his most precious of character traits. His soft voice and carefully chosen words were never cross or unkind. At least two times every day, I would be able to greet my uncle as I would enter his house before milking our cows. He became my constancy, my anchor, as I grew from a small child into the man I am today.

On this particular night almost 30 years ago, in 1990, my uncle Jerry was cutting the first crop of hay. The tall grass makes this cutting the most difficult on the equipment. Constant attention must be given to the rotating wheel and hay knives that were prone to clogging.

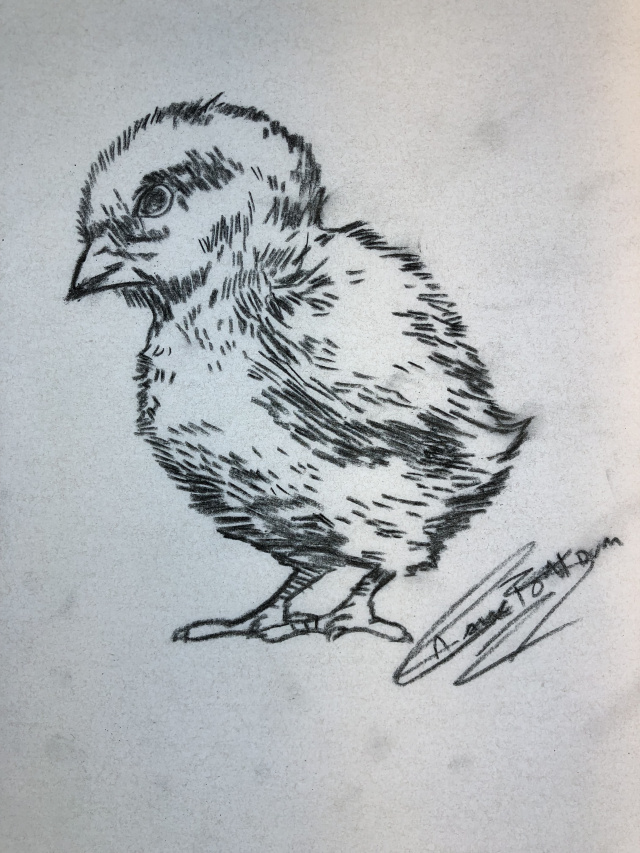

This time of year, hen Ringneck pheasants are on their nests. They sit so still that even the loud rumbling of a tractor and the ground tremors of the hay cutter leave her undeterred. Occasionally, these hens are injured or killed as they sit on their eggs. The nest, whether it be full of chirping hatchings or incubating eggs, is left to the merciless predators from the air and the nearby fortress of trees and Russian Olives that run along Cottonwood Creek.

As the sun faded behind the towering cliffs of Horn Mountain, I stood on my parents lawn, looking eagerly at the approaching two-toned tan GMC Sierra. My hero was coming home for the night.

As Jerry exited his truck, he held under his arm a brown paper grocery bag. His long stride headed towards me instead of his house across the street.

As he approached, he called my name.

“Isaac,” his low and gentle voice called, “I have something for you.”

He handed me the brown paper bag. Inside, a green towel was wrapped gently around 8 medium sized olive colored eggs.

“These are pheasant eggs,” he continued, “and they need to be cared for.”

“Isaac, I know that you will do a good job at taking care of them.”

I looked in the sack as Jerry walked back across the street and into his house.

“How do you hatch pheasant eggs?”, I wondered as I entered my parent’s house.

My incubator was nothing special, just a Styrofoam box with a small heater inside. Knowing that peasant eggs incubate for 23 days, I set the temperature and humidity and carefully laid the eggs inside.

I faithfully turned the eggs three times a day for three weeks.

Somehow, the incubation was successful and the eggs all hatched out. The tan chicks had dark brown stripes that ran parallel along their backs.

I was overjoyed when I told my uncle Jerry about my accomplishment.

“Uncle Jerry,” I exclaimed, “I did it! The eggs hatched!”

“That is great!”, he responded, “Isaac, I knew you could do it.”

His response and validation filled my system with light and my soul with joy.

The world with all of its power and wisdom, with all the gilded glory and show, its libraries and evidence, shrink into complete insignificance when compared to the simple lesson of the fragility and value of life that my uncle Jerry taught me that warm summer evening.

Over the years, uncle Jerry repeated this phrase to me. As I graduated high school, college and eventually veterinary school, his reassurance illuminated my understanding of my potential and his unwavering love and support.

There are days that change the times and there is a time to say goodbye. My sweet uncle Jerry passed away in late 2016. His loss left a tear in the eye and a hole in the heart of all my family members.

There is a place beyond the clouds, in the cinnamon sky to the west of Castle Dale, where a precious angel flies.

Somethings never change. Yet, there are things that change us all. This experience changed me.

My uncle Jerry’s lesson, from long ago, was not lost on me.

Each and every day, I remember the immense value of life, as I attend to my four legged patients.

As lives are saved and others are lost, I remember how important it is for someone to take initiative and to tend to the responsibility to care for the helpless and to speak for those without a voice.

This is a lesson my dear uncle Jerry so effectively showed me how to apply and live, and it is a responsibility I take most sacredly.

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM