My Take Tuesday: The Society for Theriogenology

Tomorrow I am traveling to Bellevue, Washington to attend the annual conference of the Society for Theriogenology. It is so nice to be able to attend in-person veterinary conferences. The past couple of years have made all of us miss out on so much that can only be experienced through in-person human interaction.

This conference is an annual event that I have attended since 2007. Each year the meeting is held in a different city around the country. I eagerly await this conference each summer.

What is Theriogenology? Theriogenology is the branch of veterinary medicine concerned with reproduction, including the physiology and pathology of male and female reproductive systems of animals and the clinical practice of veterinary obstetrics, gynecology, and andrology. It is analogous to the OBGYN, Neonatologist and Andrologist of human medicine – all combined in a single broad specialization. From antelope to zebras, Theriogenologists work on all species of animals. It is a challenging, unique and rewarding discipline.

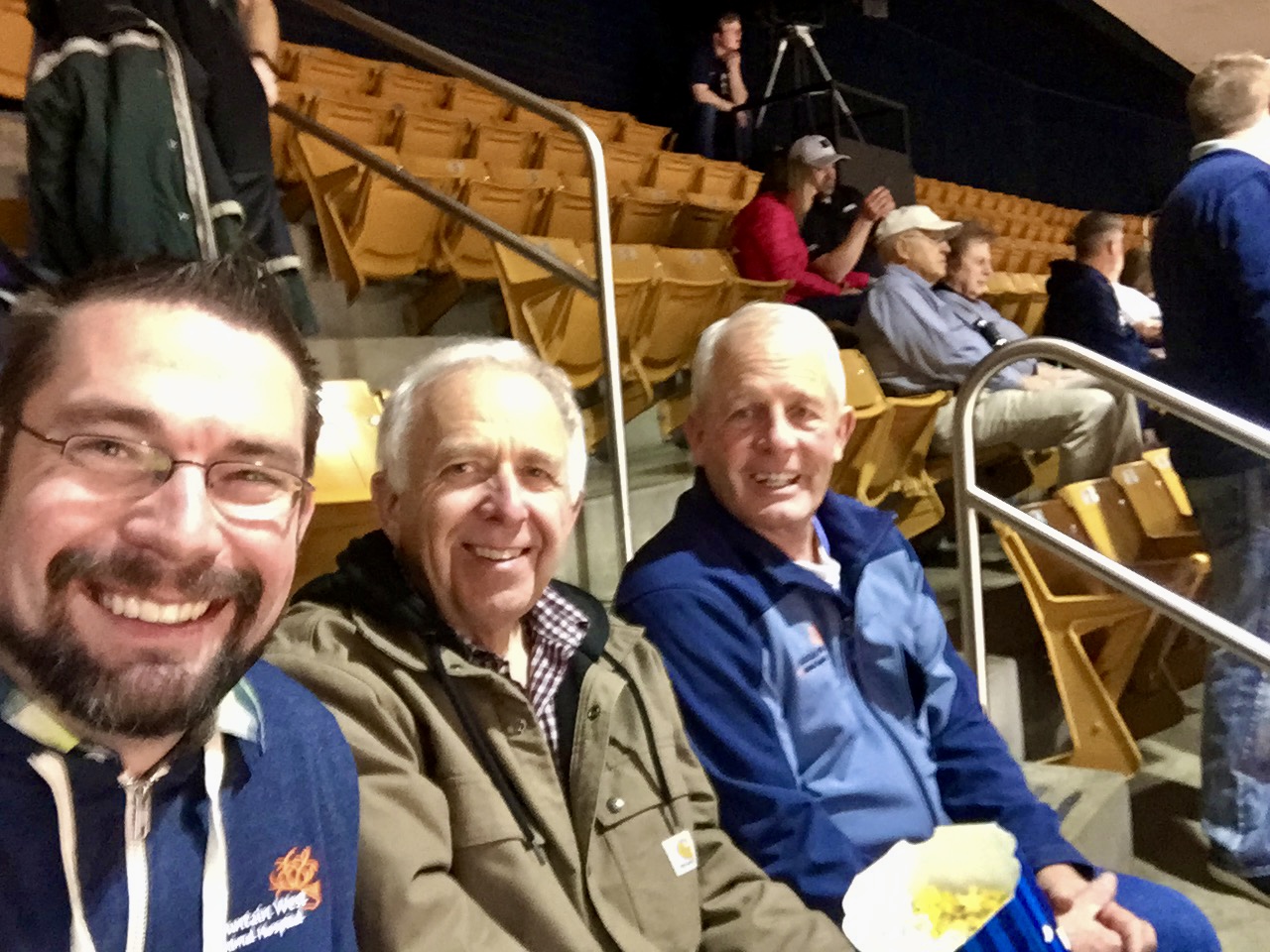

I became interested in theriogenology as an undergraduate at Southern Utah University. A professor and mentor named Dan Dail introduced me to this most unique area of veterinary medicine. I learned a lot from him. He entrusted me with a research project looking at the correlation of body condition scores and first service conception rates in heat synchronized beef cattle. His mentorship, along with this research contributed to my acceptance into veterinary school.

At Washington State University, I had the privilege of working extensively with Ahmed Tibary, a world renowned theriogenologist. He has made endless contributions in teaching, published books, chapters and scientific articles. His comparative approach taught me how to think and reason through difficult cases. He also entrusted me with the animals under his care. We published a significant amount of information on reproduction in alpacas. I remember with fondness my time working with him.

My theriogenology work has made me a better veterinarian. My clinical approach has been shaped and molded by the examples of so many mentors and teachers. What drives me is the comparative medicine; that’s what makes my brain move. Whether I am in the clinic working on dogs or cats, or out working with bighorn sheep, elk, alpacas or water buffalo, I am doing what I love.

Upon a cabinet in the lobby of Mountain West Animal Hospital, a small statue sits. The statue depicts a bull named Nandi. Nandi is the white bull which symbolizes purity and justice in Hindu art and serves as the symbol of fertility in India. It is a Bos indicus bull anointed with gold and silver jewelry and its association in Hindu art and scriptures can be traced to the Indus Valley Civilization where dairy farming was the most important occupation. There are a numerous temples in India dedicated solely to Nandi.

This statue was awarded to me after serving as president of the Society for Theriogenology in 2018. It is one of my most prized possessions. I am humbled by the opportunities that have came my way over the years as I have interacted with this unique group of veterinarians.

Kindness is a commonality among veterinarians who are reproductive specialists. They are approachable and humble. In a profession where arrogance often is the norm, they are a refreshing example of the best of the best. They are among the leadership at nearly every veterinary school in North America. They are leaving a lasting impression on the profession.

I am so proud to be a member of this group.

This is by far my favorite conference to attend. I look forward to learning from the best in the world this week and I can’t wait to apply what I learn at my own veterinary practice.

And that is my take.

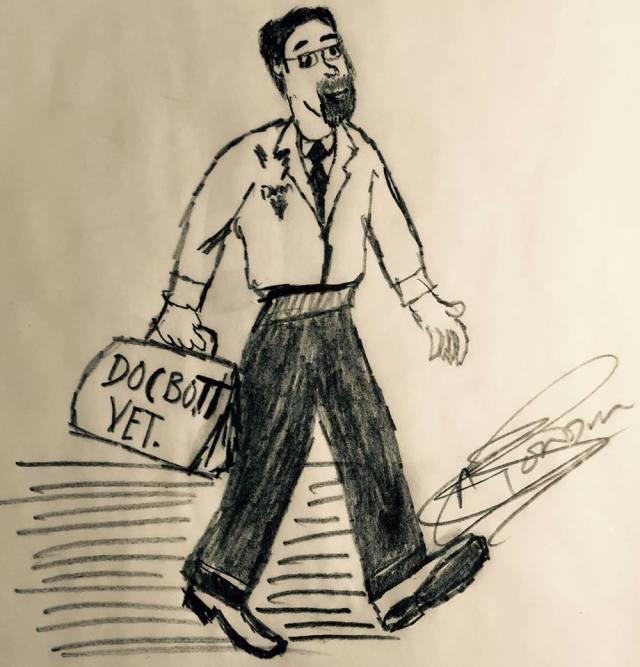

N. Isaac Bott, DVM