My Take Tuesday: The Tale of the Tail

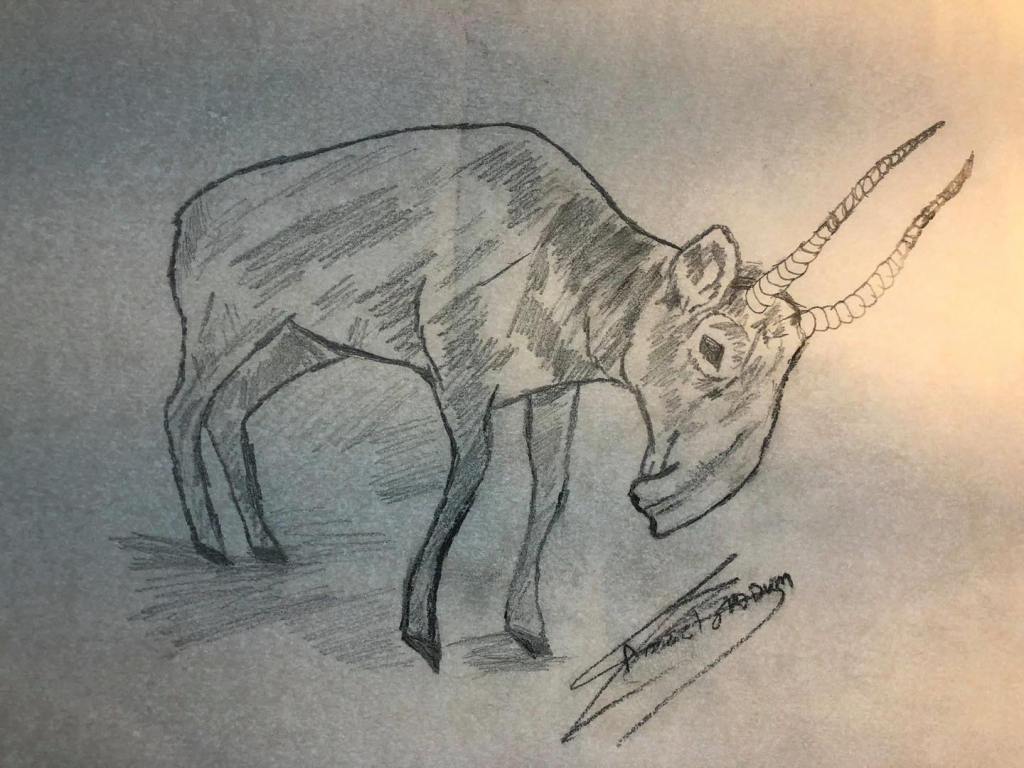

While growing up on a small farm in Castle Dale, my usual day began at 5:00 AM. My family owned 2 Guernsey milk cows. Their names were Mahana and Mokey. Dairy cows are milked either two or three times a day on most dairy farms. We elected the twice daily milkings which we spaced out evenly in a 24 hour time frame. My older brother and I would take turns milking each of them. I would milk Mahana in the morning and Mokey in the evening.

Although born as twins, each cow had distinct capricious personalities. Dealing with Mokey was a roll of the dice. She was unpredictable and instantly agitated. She was able to place a forward kick from her rear right leg precisely in the milk bucket or the center of my shin as she desired. Her eyes bulged out the side of her head, she always had a wild look and seemed to be able to track every move I made before it happened.

Mahana was docile and aware of her surrounding at all times, she could transition from tranquility to rage in a split second. She seemed to be swooshing her tail constantly. Her tail would connect against the side of my face. Although frequent bombardment from flies would initiate this torture, she quickly learned that her tail was a weapon capable of inflicting pain and discomfort. She would constantly whip my face with the coarse hairs at the end of her tail, which was analogous to a lashing from a bullwhip. Accumulations of feces and mud made on the distal end of her normally soft tail hair would transform her tail into a rigid and most dangerous weapon. After enduring this month after month, I decided that it was time to do something about it. The tail needed to be controlled and contained… But how?

Tail docking was out of the question, although an inconvenience for me, her tail was important for her, particularly during the warm months of summer when flies and other biting insects abound.

My first idea was to shave the dangerous hair off the end of the tail. This would clearly remove the most painful part of the ordeal. I used an old pair of electric clippers and shaved the tail.

That afternoon, I sat down on the milking stool and began the normal routine, assuming my intervention would be successful. Almost immediately, her tail came flying towards me. Unable to duck out of the way I just leaned into it. The shaved tail landed across my cheek and left a large welt. It felt like I had been slapped with a stiff garden hose. The pain was considerably greater than that caused by the tail hair. I realized that I had unknowingly created an even more formidable weapon.

My second idea was to develop an anchor to which I would tie the tail. This would prohibit the tail from reaching my face. I searched for an object to which I could anchor her tail to. I found a cinderblock that seemed to fit the part.

Having been a boy scout for years, I knew how to tie a good knot. I used orange bailing twine to tie the secure knots connecting the tail to the cinderblock anchor. There was no way the knot was going to come undone.

Many may wonder just how strong a cow’s tail really is. How much weight can it lift? Well, that day I learned a painful lesson, and I can attest that a cow’s tail can indeed easily lift and swing a cinderblock.

The solution to the problem was simply anchoring the tail to the back leg of the cow. Ironically, it took a cinder block to lead my simple mind to the even simpler solution.

And that is my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM