My Take Tuesday: The Capricious Caprine

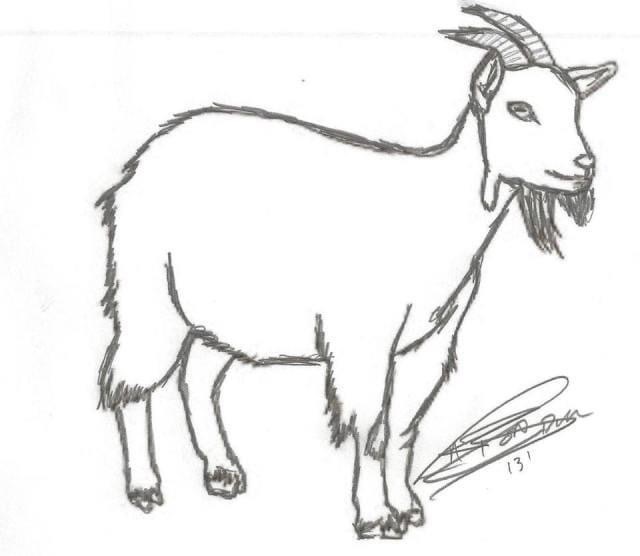

We are all familiar with the classic Norwegian folk tale of the “Three Billy Goats Gruff.” The captivating children’s story follows an “eat me when I am fatter” plot. The intelligent goats cleverly deceive the hungry troll to access the greener pastures on the other side of the bridge. This species is often overlooked, but its importance on world agriculture is tremendous.

Goats are one of the oldest domesticated species, and have been used for their milk, meat, hair, and skins over much of the world. Goats have an intensely inquisitive and intelligent nature; they will explore anything new or unfamiliar in their surroundings. They do so primarily with their prehensile upper lip and tongue. This is why they investigate items such as buttons, rope, or clothing (and nearly anything else!) by nibbling at them, occasionally even eating them.

Goats will test fences, either intentionally or simply because they are handy to climb. If any of the fencing can be spread, pushed over or down, or otherwise be overcome, the goats will escape. Due to their high intelligence, once they have discovered a weakness in the fence, they will exploit it repeatedly.

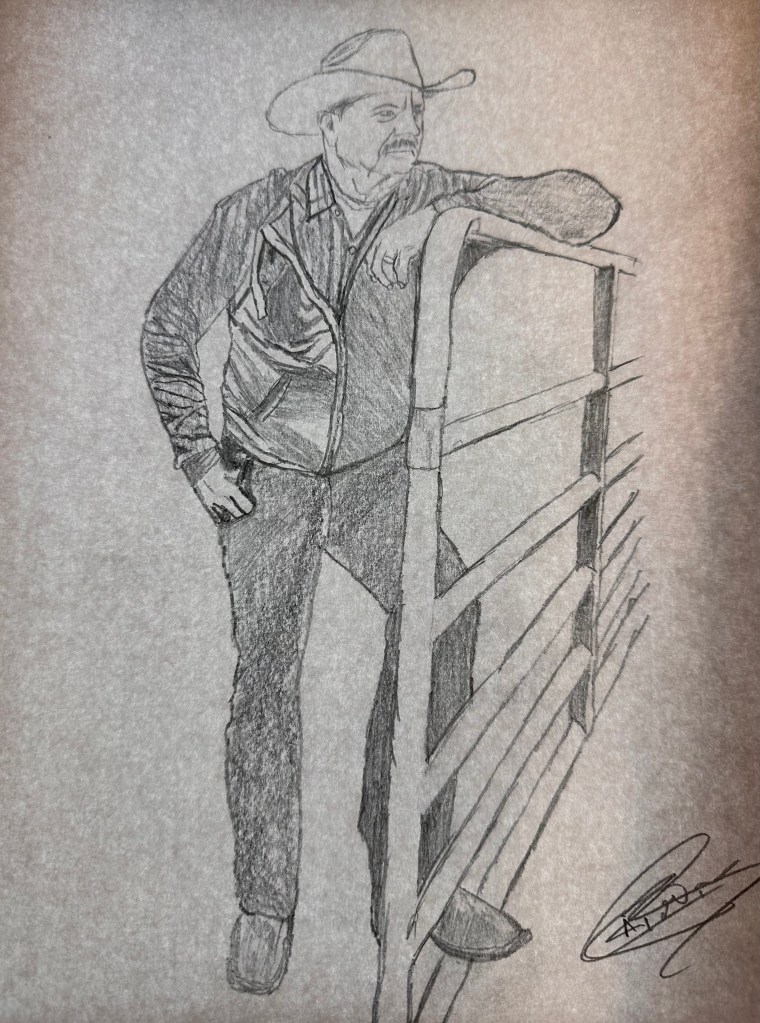

To help illustrate my point, I will share with you a lesson I learned as a teenager growing up in the small town of Castle Dale, Utah.

One summer I was entrusted with the care of a small herd of goats belonging to a disabled veteran. Each morning and afternoon, I would travel down Main Street to the small white house on the corner near the hardware store. The most vocal and dominant goat in the group I affectionately called “General Custer” because of a small unusual patch of hair extending forward from his beard.

General Custer could escape his pen without leaving any evidence as to where the weak spot in the fence was located. Several times a week I would find the devious billy goat in the yard of the house nibbling on the freshly bloomed flowers. Each time this event occurred, I would take him back to his pen, where he would remain, albeit temporarily, satisfied.

One morning I got in my car, a 1979 white Buick LeSabre, and started the one mile drive down Main Street. As I proceeded, I noticed a large group of people gathered outside the only tavern in the small town of 1,500 residents. I noticed several men laughing and looking down the sidewalk. As I approached, I noticed a goat standing next to the front door. The goat had a rope halter on and was tied to a power pole on the sidewalk in front of the building. I continued driving, not giving a second thought to what I had just witnessed; after all, I had seen similar things growing up in a small town.

As I arrived at the small house to feed the goats, I immediately noticed that the General was not in the pen. I began looking around the yard for the wayward caprine. He was nowhere to be found.

As I frantically began running through the possibilities in my mind, I remembered the goat that was tied up at the bar. I jumped back in the car and drove as quickly as possible back to where the goat was tied up previously. The crowd had entered the bar and General Custer stood calmly tethered to the pole, chewing his cud and very much unaware of his situation. I jumped out of the car and quickly untied the escapee. I did not have any way to haul General Custer and the 1/2 mile walk back to the house would be awful leading a goat. The large back seat of the Buick would have to do. I placed the general inside the car and headed back down Main Street with the billy goat bleating at every car and pedestrian we passed.

Naturally, the stench in the days following the incident with General Custer was such that the windows needed to remain down while traveling. It took months to rid the car of the goat eau de toilette that so effectively had permeated the back seat.

I was proud of myself. The General had escaped and wandered several blocks down a busy road and still came away unscathed. I had no concern for the inebriated witnesses at the bar; after all, it would be hard to believe the story in the best of circumstances.

The following week when I received the weekly local newspaper in the mail, I was astounded to read the headline on the front page of the Emery Country Progress. A picture of the tied up General was under the headline, “Goat on the Loose”. It seemed that a goat was found wandering the streets of town and that a group of concerned citizens had caught and tied up the animal. The article explained that the male goat had mysteriously disappeared before local animal control authorities had arrived.

Fortunately, someone had taken a picture to corroborate the unlikely story…

And that is my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM