My Take Tuesday: White Lightning

Reindeer rarely struggle during birth. Nature has shaped them for survival in harsh places, gifting newborn calves with an astonishing vitality—they can wobble to their feet within minutes of entering the world.

Yet even with this resilience, danger lurks. Predation remains the leading cause of death in newborn calves. To counter this, reindeer have evolved a remarkable strategy: the cows synchronize their calving. When dozens of calves hit the ground at once, predators become overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of potential targets, dramatically lowering the risk for any single newborn. It’s brilliant biology at work—but in domesticated herds, synchronized calving can present its own challenges. Every now and then, a calf arrives too early, lungs still immature, and its fight for life begins the moment it takes its first breath.

Each year I perform several artificial inseminations on reindeer, and the calves born from these efforts are especially precious. We pour heart and time into giving them every possible advantage.

A few summers ago, one of those calves made an unforgettable entrance. He was a handsome young bull with a snow-white blaze on his nose, and we were smitten from the start. His presence was magnetic—one of those animals you can’t help but root for.

But within minutes it was clear something wasn’t right. His breathing was shallow and strained, the unmistakable sign of underdeveloped lungs. Premature calves often lack surfactant, the slippery, essential substance that reduces surface tension in the lungs and keeps alveoli—the tiny air sacs where oxygen exchange happens—from collapsing. Surfactant production ramps up late in gestation, so for preemies, every breath becomes a herculean effort.

Our treatment options were limited. Synthetic surfactant works wonders but comes with a price tag and a six-hour window that put it out of reach for most veterinary settings. Without it, the best lifeline is an oxygen chamber—essentially a neonatal ICU for calves—paired with intensive supportive care.

We nestled the little bull into the chamber and got to work. Feedings came every two to three hours. Monitoring was constant. The first stretch was nerve-wracking, each rise and fall of his tiny chest a small verdict on how the next hour might go.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly at first, things began to turn. His breaths deepened. His energy lifted. His will to live—always the wild card—proved strong.

Against the odds, he made it.

We named him White Lightning, after the bold streak across his nose and the spark he carried inside.

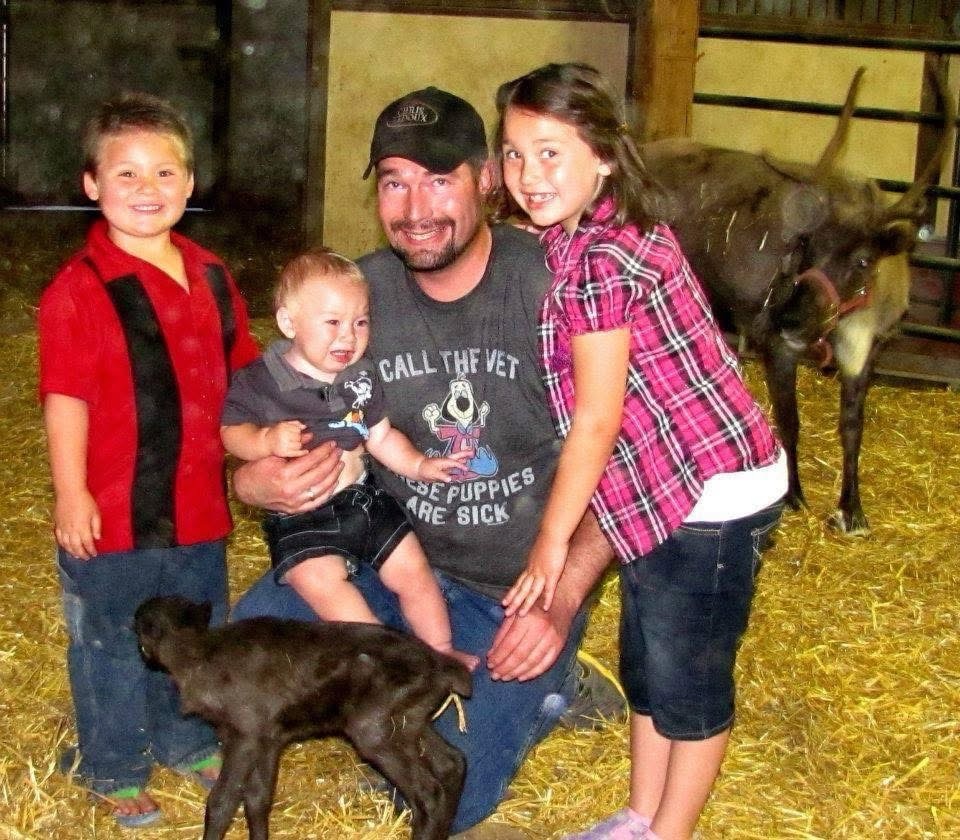

The day he turned the corner felt like a gift. We all gathered to celebrate, and even my youngest son, Kendyn—who at the time harbored a mild but persistent fear of reindeer—joined the moment. In the photo, he is very clearly crying, still convinced that reindeer are enormous, antlered monsters masquerading as cute livestock. (I’m pleased to report that he has since overcome his fear of reindeer.)

That summer, White Lightning reminded us that medicine isn’t just science—it’s heart, teamwork, timing, and sometimes a touch of grace.

And that is My Take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM