My Take Tuesday: Chickens

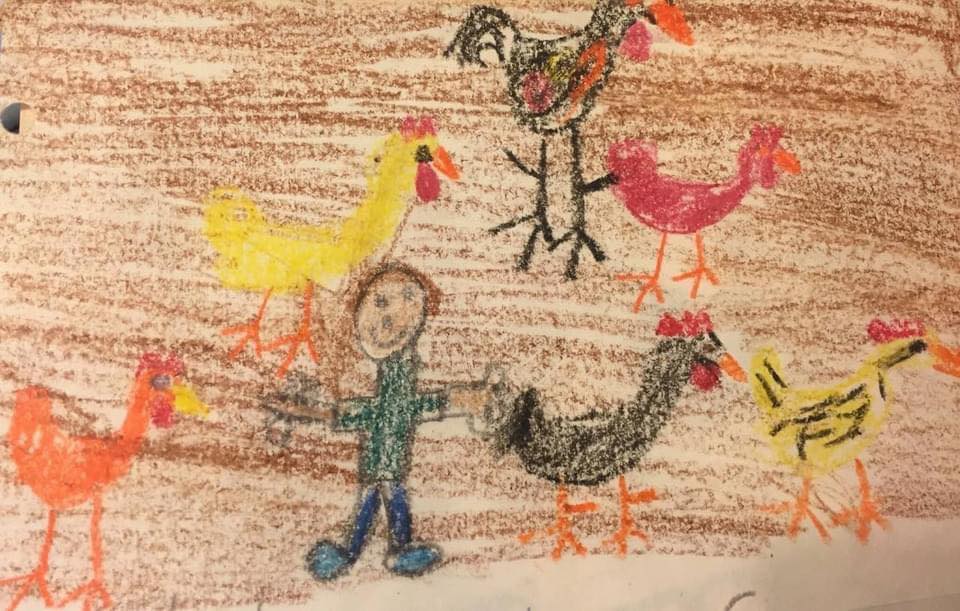

If you went to elementary school with me, you probably remember my chicken obsession. While other kids were sketching superheroes or race cars, I filled my pages with hens and roosters. Every art project turned into a poultry portrait—hundreds of them, all mediocre, all mine. Thankfully, my teachers were patient enough to let me draw to my heart’s content, even if my artistic ability never quite lived up to my enthusiasm.

Each year, the highlight of my spring arrived in the form of the Murray McMurray Hatchery catalog. Glossy pages showcased every imaginable breed—silkies, frizzles, bantams, and standards—each with its own unique traits: comb type, feathering, temperament, productivity. I pored over those descriptions for hours, weighing the pros and cons as carefully as a Wall Street investor. My parents allowed me to choose one chick per year, and that single decision felt monumental.

Picking the right chicken is no small task. Climate, egg or meat production, foraging ability, predator awareness, broodiness, even personality—all must be considered. I took the process seriously, and in doing so, learned to research, compare, and commit.

One of the most fascinating things about chickens is how they reach our homes in the first place. Here in the U.S., the postal system has, for decades, delivered day-old chicks across the country by Priority Mail. At first glance, it seems cruel—tiny birds shipped without food or water. But nature has built in an incredible adaptation: just before hatching, a chick absorbs the last of the yolk’s nutrients, giving it enough sustenance to survive up to three days. In the nest, this allows the mother hen to wait until all her eggs hatch before leading her brood away. What looks like a logistical miracle is really biology at its finest.

And chickens aren’t just fascinating biologically—they’re surprisingly intelligent. Like humans, they see in full color. Studies show they grasp object permanence (knowing something exists even when it’s out of sight), recognize more than 100 individual faces, and can remember them months later. They even demonstrate self-control for future rewards—something once thought unique to primates. Some research suggests they understand numerosity and can perform simple arithmetic. In short, there’s a lot more going on behind those beady eyes than most people realize.

Even now, chickens remain my favorite animals. After a long day at the clinic, I’ll often stand in the back yard, just watching my flock forage and explore. Their curiosity and social quirks never fail to bring me peace.

I often think back to those carefree days in elementary school—crayons in hand, sketching chickens at my desk. Time paints those memories in brighter colors, but the joy was real then, and it’s real now. My drawings may have been clumsy, but they captured something important: a fascination that has never left me.

And that is My Take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM