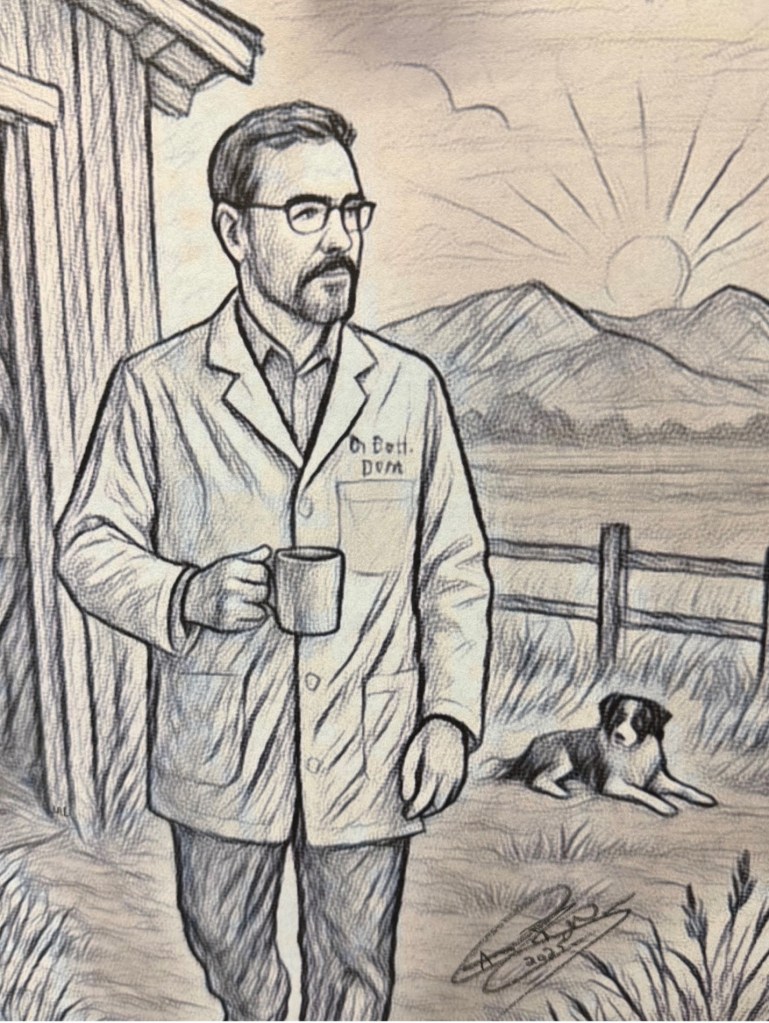

My Take Tuesday: The June Morning Awn

The clock read 4:27 a.m. when my phone buzzed on the nightstand, breaking the fragile stillness of early summer. I rubbed the sleep from my eyes and answered. Early morning calls like this are an unwritten rule of veterinary life—crises seem to wait until the world is quiet.

“Dr. Bott,” I said, already bracing myself.

“Doc, it’s Marcy. Sorry to wake you, but it’s Bandit. He’s struggling to breathe.” Her voice was tight, her words shaky.

Bandit was her six-year-old Border Collie—the kind of dog who’s more than a pet. He was her shadow on the ranch, her confidant, and, truth be told, her best friend. I didn’t need more details.

“I’m on my way,” I said, pulling on jeans and a button-up shirt, then grabbing my truck keys from the counter.

The roads stretched out before me, dark but warm, the coolness of night already beginning to yield to the rising heat of the day. Cottonwood fluff danced in the headlights, and a mourning dove’s doleful call echoed from somewhere in the distance. Even at that hour, there was a quiet splendor in the world—though my thoughts were fixed on Bandit.

Marcy was waiting as I pulled into the ranch yard, her silhouette framed by the light of the barn. She didn’t say much—just nodded and led me inside.

Bandit lay on a bed of straw, his chest rising and falling in short, strained bursts. His eyes met mine with a mixture of trust and desperation. I knelt beside him, gently feeling his throat, listening, watching. His breathing was ragged, whistling with every inhale. A small trickle of blood stained the fur beneath his left nostril.

“This isn’t his throat,” I murmured. “It’s higher up—likely his nose.”

Marcy looked at me, searching for answers. I gave Bandit a mild sedative and carefully guided an otoscope cone into his nostril. Sure enough, there it was—a slender, barbed foxtail awn lodged high in his right nasal passage, angled like a fishhook waiting to do more damage with every breath.

Foxtails are the seed heads of certain grasses—harmless enough when swaying in a field, but dangerous once they dry. By June, Utah fields are full of them. Their design is sinister: tiny barbs that drive the seed forward and prevent it from backing out. Dogs can inhale them, step on them, or get them lodged in ears and eyes. Once embedded, they keep migrating—piercing tissue and carrying infection with them.

With long forceps and a steady grip, I eased the awn free. It was no longer than an inch, but it had nearly turned deadly. The change was immediate. Bandit’s breathing slowed. His body relaxed. His tail gave a few weak but joyful thumps against the straw.

Marcy dropped to her knees beside him and buried her face in his fur.

“Thank you, Doc,” she whispered. “I don’t know what I’d do without him.”

I lingered for a few more minutes to make sure he was stable, sipping the hot chocolate Marcy had brought me. As I stepped out of the barn, dawn was in full bloom. The sky, brushed in hues of apricot and rose, cast golden light across the hayfields. Dew glistened on the fence lines. The world didn’t just wake up—it unfurled.

Driving home with the windows down, the air smelled of sagebrush and fresh-cut hay. A single foxtail seed had nearly unraveled Bandit’s world—and Marcy’s. It was a quiet reminder of how the smallest things can matter most.

So here’s my advice to dog owners this season: avoid tall, dry grasses if you can. Check paws, ears, and noses. Watch for sneezing fits, pawing at the face, or repeated head shaking. And if your dog just doesn’t seem right, don’t wait—a foxtail might be to blame.

At the heart of this work, it’s never just about removing a grass awn. It’s about restoring peace to the people and animals who depend on each other.

And that’s my take.

N. Isaac Bott, DVM