My Take Tuesday: White Lightning

Reindeer rarely encounter complications during birth. Nature has endowed these remarkable animals with incredible vitality, allowing newborn calves to stand within minutes of being born.

Despite this resilience, predation remains the leading cause of death in newborn calves. To mitigate this risk, reindeer cows synchronize their birthing cycles. By delivering their young at the same time, the herd overwhelms predators with sheer numbers, reducing the chance of individual losses. This natural strategy is fascinating but poses unique challenges for domesticated herds. Occasionally, calves are born prematurely with underdeveloped lungs—a condition that often proves fatal.

As a veterinarian, I perform numerous artificial inseminations on reindeer each year. The calves born through this process are especially valuable, and they receive meticulous care to give them the best possible chance of survival.

A few summers ago, a particularly memorable calf was born. He was a striking young male with a distinctive white marking on his nose, and we were instantly smitten. His charm was undeniable, and he quickly became a favorite among all of us.

However, it soon became clear that something was wrong. The calf struggled to breathe, a telltale sign of underdeveloped lungs. Premature calves often lack surfactant, a critical substance that reduces surface tension in the lungs and stabilizes the alveoli (the tiny air sacs responsible for oxygen exchange). Surfactant production typically begins in the womb, but when calves are born prematurely, this process may be incomplete, making every breath a challenge.

Treatment options for surfactant deficiency in veterinary medicine are limited. Synthetic surfactant therapy, while effective, is prohibitively expensive and must be administered within six hours of birth. Without it, the best alternative is placing the calf in an oxygen chamber—similar to those used for human neonates—while providing intensive supportive care.

We carefully placed the little calf in the oxygen chamber and monitored him closely. Feeding was required every two to three hours, and the first several hours were touch and go. But gradually, his tiny lungs began to strengthen, and his breathing improved.

Against the odds, this determined calf survived. We named him White Lightning, a tribute to the bold white stripe on his nose.

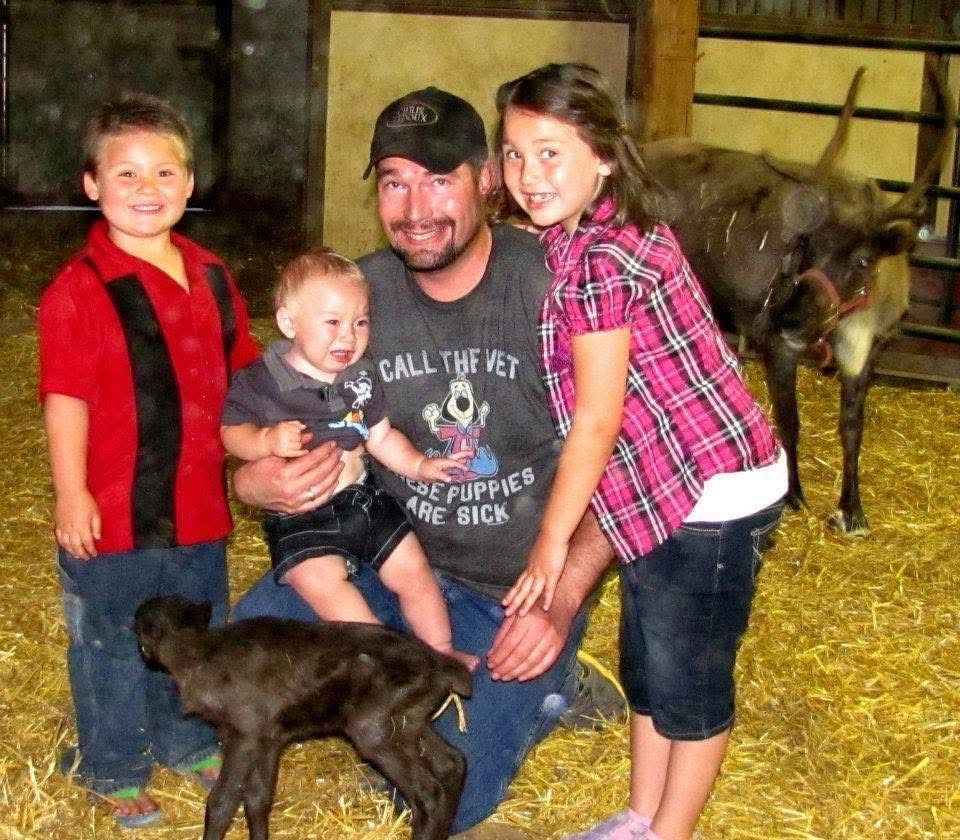

That summer day, we witnessed a small miracle. As the photos show, our entire team celebrated his recovery. Even my youngest son, KW, who had a lingering fear of reindeer, joined in—though his enthusiasm was a bit reserved in the picture. (I’m happy to report that KW has since overcome his fear!)

And that’s my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM