My Take Tuesday: The Saga of the Saiga

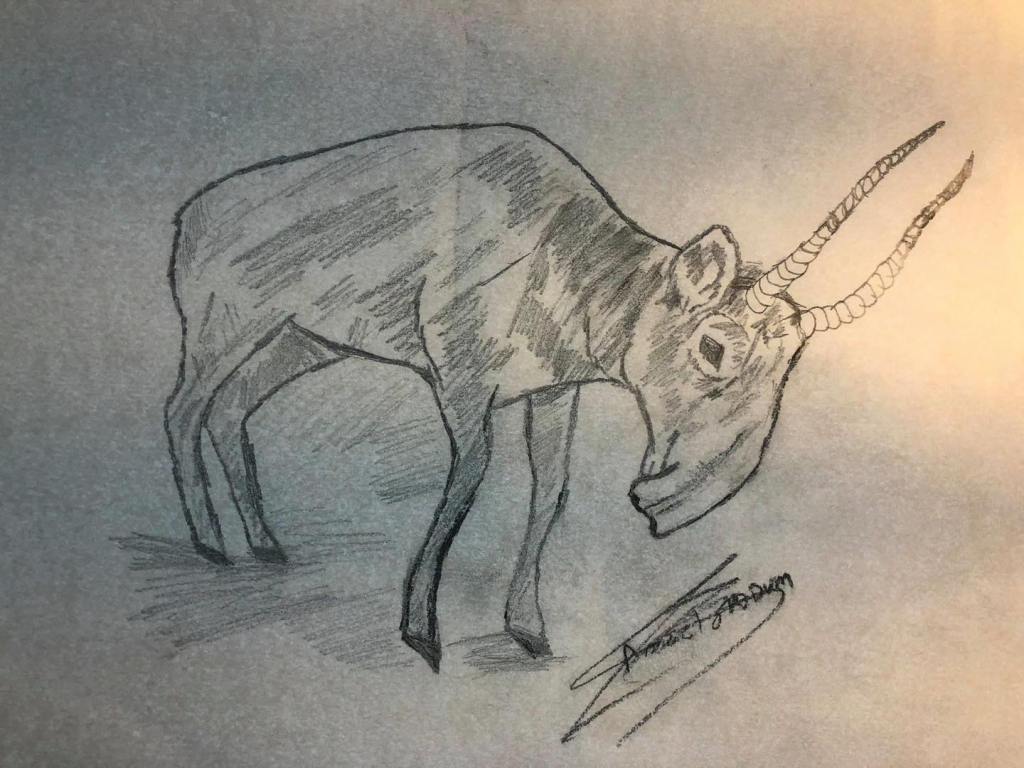

They look like something you would read about in a Dr Seuss book. From their long exaggerated proboscis to their loud nasal roars; this species is truly unique. Their bulbous noses, which hang over their mouths, give these antelope an almost comical appearance. The nose is flexible and can be inflated, helping them to breathe warm air in the freezing winters and filter air in the arid summers as they sprint with their heads down in a cloud of dust. Two considerable populations exist today. Kazakhastan is home to the largest population and a second, smaller group resides in Mongolia. Over the past few decades, they have made a population comeback. But this all changed recently and now they are in grave danger.

There was almost something biblical about the scene of devastation that lay across the wide-open fields in the wilderness of the Kazakhstan steppe. Dotted across the grassy plain, as far as the eye could see, were the corpses of thousands upon thousands of saiga antelope. All appeared to have fallen where they were feeding.

The saiga in Kazakhstan – whose migrations form one of the great wildlife spectacles – were victims of a mass mortality event, a single, catastrophic incident that wipes out vast numbers of a species in a short period of time. These Mass Mortality Events are among the most extreme events of nature. They affect starfish, bats, coral reefs and sardines. They can push species to the brink of extinction, or throw a spanner into the complex web of life in an ecosystem.

When this event occurred in 2015, over 200,000 (more than half the total population) died due to a mysterious illness. This mass die-off baffled both veterinarians and scientists as they scrambled to identify the cause. The culprit was identified as a bacteria called Pasteurella multocida. This bacteria normally lives harmlessly in the tonsils of some, if not all, of the antelope. It is thought that an unusual rise in temperature and an increase in humidity above 80% in the previous few days had stimulated the bacteria to pass into the bloodstream where it caused haemorrhagic septicaemia, or simply put – blood poisoning.

In 2017, the saga population in Mongolia was devastated by a viral disease. Called peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV), this virus originated in sheep and goats and quickly spread through the Mongolian Saiga population.

PPRV, which is also known as sheep and goat plague, is highly contagious and can infect up to 90 percent of an animal herd once introduced. After just a few days affected animals become depressed, very weak, and severely dehydrated. This devastating illness swept trough the saga population, leaving over two-thirds of the critically endangered animals dead. The remaining population in Mongolia has been vaccinated in an effort to prevent further outbreaks.

Mass mortality events are not unusual for saiga antelope. However, the scale of the current events are unprecedented relative to the total population size. Warmer weather patterns, coupled with increased humidity, played a key role in causing the outbreak of hemorrhagic septicemia in Kazakhstan. Often these mass mortality events also occur in the birth period, when Saiga females come together in vast herds to all give birth within a peak period of less than one week.

Sometimes the answer to saving a species involves exportation, sequestration and assisted reproductive technologies to enhance genetic diversity. In my opinion, this is key to save the saiga antelope.

The saiga antelope is truly unique. They existed at the same time as the sabertooth and wooly mammoth. They are a relic of the past.

I hope we can save this species. They are truly remarkable!

And that’s my take!

N. Isaac Bott, DVM